People are disappearing in the world of writer/director Alex Garland. In his screenplays with director Danny Boyle, humanity is always finding itself more and more isolated, whether by choice or contingency. Whether it’s an uninhabited island in The Beach, the vast empty streets of London in 28 Days Later, or the diminishing inhabitants of a ship drifting in the emptiness of space in Sunshine; people exist in specific pockets in his world, desolate places where they must do battle with themselves and the ramifications of the human condition.

A similar recession into mysterious isolation, where characters come to terms with monstrous truths, can also be seen in the two films Garland has directed. His acclaimed debut Ex Machina (one of the first great A24 films) concerns a very small group of ‘people’ in a tech billionaire’s mansion, and his arguably superior follow-up Annihilation follows a similarly condensed team diminishing in number as they traverse a horrific, metaphysical zone. Humanity continues to recede in Garland’s new film with A24, Men.

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

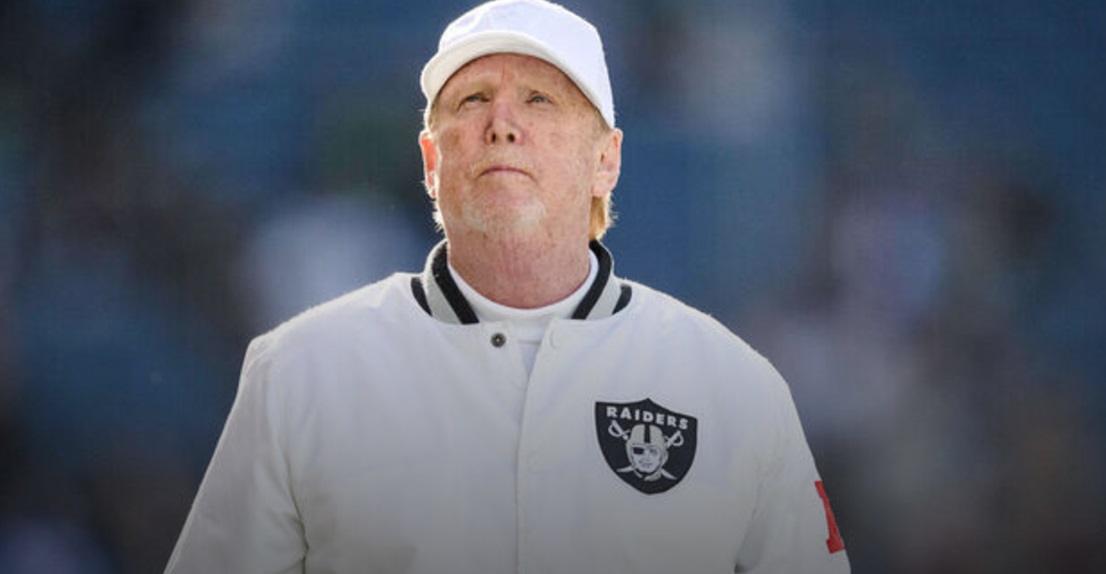

Alex Garland’s Menacing Men

A24

In his most metaphorical use of an isolated space to date, Garland has now essentially created the world of a woman’s mind, populated by numerous characters all played by the same actor. A few other characters appear, but they almost never have any physical proximity; a woman exists in digital space on a phone screen, and a dead lover is merely a flashback apparition. No, Men is all about Harper Marlowe, and all the men surrounding her are simply variations on the theme (or threat) of masculinity, at least in Harper’s eyes.

The film follows Harper on what’s supposed to be (and, in cinema, rarely is) a comforting trip to the countryside after her husband James’ suicide. While she knows (logically) that she isn’t responsible for his death, she nonetheless feels (psychologically) a sense of guilt; she had just told James that she wanted a divorce, and James had threatened Harper that he’d take his own life if she went through with it. There’s a strong narrative sense that the entirety of Men takes place in these moments leading up to and including the suicide, which are revealed throughout the film in tandem with the ‘actual’ action of Harper’s holiday.

Related: Men Early Reactions Praise Alex Garland’s Eerie, Surreal, Uniquely Terrifying Vision

Harper is staying in a spacious and allegedly 500-year-old house in a rural area, which is introduced to her by Geoffrey, an eccentric man who reminds her not to flush any tampons in the first of many subtle sequences of sexism (or at least gendered discomfort). Harper wanders the woods and discovers a cavernous and caliginous tunnel, wherein she has a bit of musical fun, harmonizing with her own echo in a richly metaphorical scene instructing the audience that Men is really a conversation between Harper and herself. To further the point, a silhouette appears at the other end of the tunnel, dressed and looking conspicuously like her from what can be gleamed in the darkness. The metaphors continue, as every man Harper encounters looks suspiciously the same and becomes increasingly threatening.

A24

Horror is famously conducive to metaphor and allegory; no other genre can deal in symbolism quite like it. This is one of the traits of the supposed ‘elevated horror’ era of films (dominated by the horror movies of A24), where cinema can address sociopolitical and psychological themes while still being bloody good entertainment. Scary movies with racial commentary, or horror films tackling political ideologies, the economics of social inequality, and the real-life traumas of women are proliferating with rapidity these days, so Garland certainly isn’t the only director maneuvering metaphor in place of plot. With Men, though, he’s delivered one of the most heavy-handed ones.

A bevy of articles written in the wake of Men have been questioning if the horror genre has perhaps gone a bit too far with metaphor, taking the ‘sub’ out of ‘subtext’ altogether and becoming so on-the-nose that they might as well be pimples. Articles like “On ‘Men’ and the Heavy-Handedness of Highbrow Horror” from Inside Hook and “Scarily Obvious: Why the Horror Genre Needs to Drop Clumsy Metaphors” from The Guardian detail how the lack of subtlety in Men’s metaphors points to this growing trend, and they’re not entirely wrong.

A24

The symbolism in Men is quite obvious, but the film is a text in dialogue with many other texts by design, purposefully referencing them in order to interrogate the way women have been the bearers of blame in narratives since the earliest days of writing. Sure, the painfully blatant metaphor of Harper eating an apple from a tree and Geoffrey joking that it’s “forbidden fruit” is quite obviously referencing Adam and Eve and the story of The Fall, but it does so with purpose. Men is pointing out that the basis for many Judeo-Christian beliefs (or at least the more conservative ones) stems from Eve’s bad decision; the woman becomes responsible for all loss of innocence and the fall of humanity from the perfect Garden of Eden.

The poetry of Samuel Daniel is also referenced, specifically his poem Ulysses and the Siren, which itself references the old Greek and Roman stories of Ulysses (or Odysseus). The ‘siren’ here is a reference to the women Ulysses and his manly crew encounter on their quest, who are so lovely and sing so beautifully that they lure men to their own demise. The subtext of Homer’s myth is also obvious — women are the ones to blame if men are attracted to them; women are the seductresses and temptresses whose beauty is inherently corrupting and malicious.

Daniels’ poem ends with the famous line, spoken by the siren (and spoken by a man in Men), “For beauty hath created been to undo, or be undone.” Female beauty, these authors suggest, is the cause of man’s undoing. “Love is a sickness full of woes, all remedies refusing,” Daniels writes in another poem. The metaphors here are obvious, but they’re exceedingly useful. A priest confronts Harper at a church with accusatory language about her husband’s suicide, asking her why she “drove him to it;” a boy calls her an expletive for not playing with him; her husband tells her that his suicide will be her fault. Is it any wonder, then, with this narrative history of blaming women for men’s own actions and disappointments, that Harper is haunted?

Alex Garland Finally Embraces the Horror Genre With Men

A24

It could be said that Alex Garland has been slowly drifting toward horror his whole life. This is almost played out in real-time in his script for Sunshine, which begins as a bona fide sci-fi drama before unexpectedly (and, to many, pointlessly) descending into pure horror. Sure, 28 Days Later is one of the best horror movies of the 2000s, but his script is more of a melancholic drama with suspenseful elements than anything else; it’s Danny Boyle, with his brilliant direction, who turns it into a horror film. The sci-fi of Ex Machina features some disturbing imagery, while Annihilation finds terrifying body horror in its sci-fi premise.

Related: 28 Days Later Writer Has Really Cool, Bigger Idea for a Sequel

Now, Garland has arguably created his first true horror film, which is more in the vein of atmospheric horror classics about women like Don’t Look Now and Let’s Scare Jessica to Death than it is to what many would call ‘horror.’ That is, until the final half-hour of Men, when all hell breaks loose. The film expertly builds its atmospheric tension until becoming an absolutely disgusting body horror gross-out which would certainly cast a grin upon David Cronenberg’s face. The imagery is so repulsive, the special effects so utterly gross, and the sequence so ridiculously long that it almost risks becoming a bizarre curiosity to watch rather than a horrifying sequence of scares.

Jessie Buckley and Rory Kinnear are Brilliant in Men

A24

Nonetheless, it’s an incredible and unforgettable finale that creates a visceral manifestation of all the metaphors which preceded it. The sequence (and the film as a whole) wouldn’t work at all if it wasn’t for the two main leads, Jessie Buckley (as Harper) and Rory Kinnear (as pretty much everyone else). Kinnear does something similar to what Tom Noonan did so wonderfully in Anomalisa, playing almost everyone in a film but managing to embody each character differently. That film, however, was stop-motion animation; in Men, Kinnear goes above and beyond by physically inhabiting these men with remarkable range. The actor, who recently shined in Our Flag Means Death, is absolutely brilliant here and proves why he needs to lead more films.

Jessie Buckley’s performance is perfect as well, and it has to be — she’s in literally every scene, and the film is an exploration of her headspace. She continues to prove why she deserves to be in many of the most interesting and bold films and television of recent years (I’m Thinking of Ending Things, The Lost Daughter, Fargo, and Chernobyl, for instance), and will surely do so again in Sarah Polley’s upcoming adaptation of Women Talking.

A24

Rob Hardy continues his cinematographic work with Garland, and it’s clear that the two have a shared visual language. The imagery is earthy, extremely textual and organic, and really immersed in the atmosphere of a creepy countryside, and the way it incorporates the grotesque special effects at the end is remarkable. How Hardy uses light in the wonderful tunnel sequence, and his incorporation of green and red colors, is especially inspired, but his work throughout goes a long way to visually solidifying Garland’s (often heavy-handed) themes.

Men’s metaphors are rather obvious, with the film as subtle as a sledgehammer in certain places, but the way it incorporates them to tell a story of a woman’s illogical guilt, and the gender which has come to terrify her, is artfully done. It’s a blatant film, but blatantly good. Men is now in theaters, and screens at the Cannes Film Festival on May 22.

The Best A24 Horror Movies, Ranked

Read Next

About The Author

Matthew Mahler

(112 Articles Published)

Editor and writer for Movieweb.com. Lover of film, philosophy, and theology. Amateur human. Contact him at matthew.m@movieweb.com

You can view the original article HERE.