“Man screams from the depths of his soul; the whole era becomes a single, piercing shriek. Art also screams, into the deep darkness, screams for help, screams for the spirit. This is Expressionism.” That’s what Austrian playwright Hermann Bahr wrote about the emerging and always evolving art movement known as Expressionism (and later Post-Expressionism), seen not just in painting but in the great silent horror films. In many ways, this art was a response to war.

During and after World War I, a variety of new aesthetics emerged to reflect the massive changes and horrors occurring in Europe. Hinterland (or Homefront), an excellent movie that is available on digital platforms and Video On Demand today, Oct. 7th, reflects that period outside the trenches better than almost any other film in decades. In one scene, as a group of artists and theorists hotly debate the new trends and declare themselves anarchists, one character says, “Communists, at best. Futurists, Dadaists, everyone’s an -ists these days.”

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

The vast amount of artistic movements which transpired around World War I is a testament to just how much was going on in Europe at that time, and Hinterland masterfully chronicles the malaise, suffering, and hopelessness which produced great Expressionist art, art that “screams for the spirit.” Hinterland screams, too.

Stefan Ruzowitzky Recreates Post-War Austria in Hinterland

Film Movement

Square One

Hinterland is directed by Stefan Ruzowitzky, who won the Best International Feature Film Oscar for The Counterfeiters. Like that film, much of Ruzowitsky’s filmography is focused on war either explicitly or tangentially, but Hinterland may be his most exhilarating achievement yet. Filmed using a great amount of blue screen technology, Ruzowitzky recreates 1920 Austria through the lens of Expressionist art. The past is a memory and history is subjective, so seeing post-war Austria play out in a digital haze is almost more honest than some expensive Spielbergian recreation of a city.

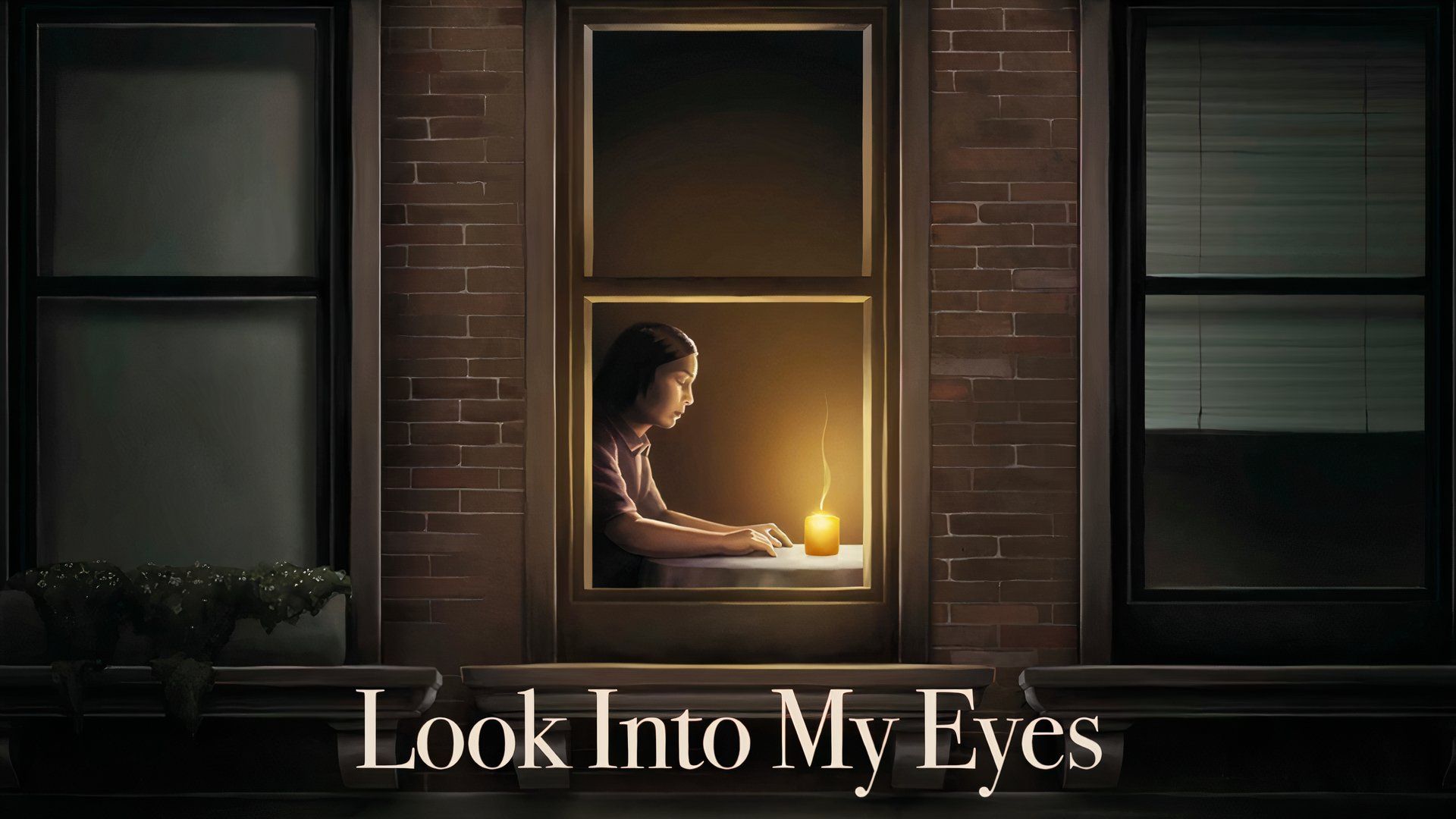

Hinterland follows Lieutenant Peter Perg as he and other soldiers return home after being held prisoners of war for two grueling years. When they left to fight in World War I, they pledged allegiance to a monarchy and were defending an empire; when they returned, that mighty Austro-Hungarian Empire had been reduced to a small, smoldering Republic. Perg had fought for an Empire which no longer existed and returned to a dissolved home.

Related: Exclusive: Hinterland Trailer Reveals Epic Post-War Thriller

He and his fellow soldiers are treated terribly on the streets of Vienna, which is strewn with wet garbage and overflowing with people. In Ruzowitzky’s digital metropolis, which is part Seven and part Dark City, buildings are just as crooked as the camera angles, and life is perpetually gray. Smoke rises in the industrial distance, lingering in the air and clouding out the sun. Soldiers wounded in the war hobble on crutches or beg on the sidewalks, and dirty children with neither parents nor home scurry through alleyways.

Hinterland and the Horrors of War

Film Movement

Square One

Perg’s wife and daughter never expected him to return home (like the one million other Austro-Hungarians who didn’t), and have fled to the countryside where there’s a higher probability of food and survival. He can’t bring himself to see them, fearing that what he did in the war (and what was done to him) has made him deranged.

He’s a haunted man, and when Hinterland scans the faces of his fellow soldiers traumatized by war, it’s clear that Ruzowitzky understands the shame of these men. “Don’t look anyone in the eyes here,” one man says in the shelter. It’s in this subtle, tacit way that Hinterland suggests why National Socialism and Nazism took hold of so many people who had lost everything and desperately needed dignity.

Perg may have lost everything, but he is the lucky one, a formerly respected detective and previously wealthy man who gets to sleep in a house rather than the streets or the crowded shelters. In this grim but beautifully imaginative technical marvel of a city, a serial killer is stalking the streets and torturing former soldiers to death, soldiers Perg used to know. The crime scenes are disturbing, stitching together an overall atmosphere of horror even if this is not a horror film. If Hinterland is horror, it’s the same way that Seven or True Detective is horror — morbid meditation on the existential dilemma and the darkness embedded within humanity.

World War I and the Death of Morality in Hinterland

Film Movement

Square One

“Killing and torturing is very human indeed,” Perg says at one point. “Inhumane? Just look at the newspapers.” Like any great war film, Hinterland interrogates the nature of violence and explores the ethical ambiguity of wartime. As Perg becomes involved with the investigation, helping out the current detective Victor Renner and the beautiful forensic criminologist Dr. Theresa Körner, he is forced to confront his traumas in an almost painfully therapeutic way. As the revelations of his past and the well-constructed mystery of the film unfolds, Hinterland asks some somberly engaging questions.

While World War I has often been cast aside in favor of the easier narratives of World War II or Vietnam, there have been a surprising amount of good movies from the past decade which focus on the period — Testament of Youth, 1917, Journey’s End, They Shall Not Grow Old, Foxhole, The Silent Mountain, and the upcoming remake of All Quiet on the Western Front.

Film Movement

Square One

Most of those (and war films in general) are focused on battles themselves, but Hinterland is able to brilliantly discuss the war and its aftermath while never journeying into the trenches. Hinterland understands that the most devastating consequence of World War I was the end of a shared morality.

“God died in the war,” one character says, and he couldn’t be more correct. This isn’t necessarily a theological statement, though; ‘God’ here means objective morality, shared humanity, a belief in the future. All of that ended with the mustard gas, trench warfare, and biological weapons of the first World War, and this is partly what paved the way for the countless future atrocities and genocides of the 20th century. At its best, Hinterland reveals these remnants of war and how they destroyed not just a universal ethics, but a part of the human spirit forever. “What we did was wrong,” one character says. “Wrong because there was no right.”

Hinterland is a Technically Marvelous Achievement That’s Now Available

Murathan Muslu is wonderful as Peter Perg, with a battered face and eyes more wounded than his body telling most of his story for us. He seems to be forever tensed; even in his big, dusty coat, Muslu’s body language is perfect, like a stern and solid thing now cracked and chipped. Liv Lisa Fries as Dr. Körner continues to be a delight in whatever’s she’s in, be it Babylon Berlin or Munich – The Edge of War. She’s light and clever but in a grounded, natural way. Even when the two actors recite lines that seem like a police procedural, they still seem organic.

Related: Some of the Best World War Two Movies From a German and Axis Perspective

The score from Kyan Bayani is perfect, its melodramatic, operatic sweep complementing the Expressionistic visuals and intensity of the plot. Benedict Neuenfels and Ruzowtizky have accomplished something very special with the imagery in Hinterland, using the blue screen technology to great effect while also creating a realistic foundation that never lets the film float off into CGI abstraction like Sin City or Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. Even if the world they create is obviously digitalized, it almost always works, hearkening back to great Expressionist films like the silent masterpieces The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis. Like them, Hinterland understands the nature (and importance) of artifice.

Film Movement

Square One

It’s usually a mess when a script has multiple writers, but Robert Buchschwenter, Hanno Pinter, and Stefan Ruzowitzky perfectly compress their thoughts into a brisk, extremely gripping 90 minutes, never outstaying their welcome. Any longer and the forbidding, bleak design of this Hinterland may have become an exercise in glorified misery. As it stands, Hinterland may be gloomy, but its brief editing, great performances, thoughtful ideas, and elaborate visuals make it a perfect post-war rumination.

Hinterland is a FreibeuterFilm and Amour Fou Luxembourg production, in co-production with Scope Pictures Belgium and Lieblingsfilm Germany, and is now available digitally and On Demand courtesy of Film Movement.

You can view the original article HERE.