The first time Tyler McCall saw plus-size models on a New York Fashion Week runway — Precious Lee and Marquita Pring at the Christian Siriano spring 2017 show — she felt . . . something. Not quite emotional, but something pretty damn close to it. It was a moment that signified a shift in the industry’s attitude: After years of advocating for more body inclusivity in fashion through her work as an editor at Fashionista, it felt like the stirrings of necessary, long overdue change.

“I could never have imagined when I was a teenager, for example, and really interested in fashion, opening the pages of Vogue and seeing a plus-size model . . . or reblogging plus-size models on the runway on Tumblr,” McCall says. “It felt good, but I’ve worked in the industry long enough to feel cautious — cautiously optimistic — about that. I’m aware of tokenism; I’m aware things can be treated as trends.”

“These shows are powerful symbols of what is fashion, what is beauty, and what is glamorous.”

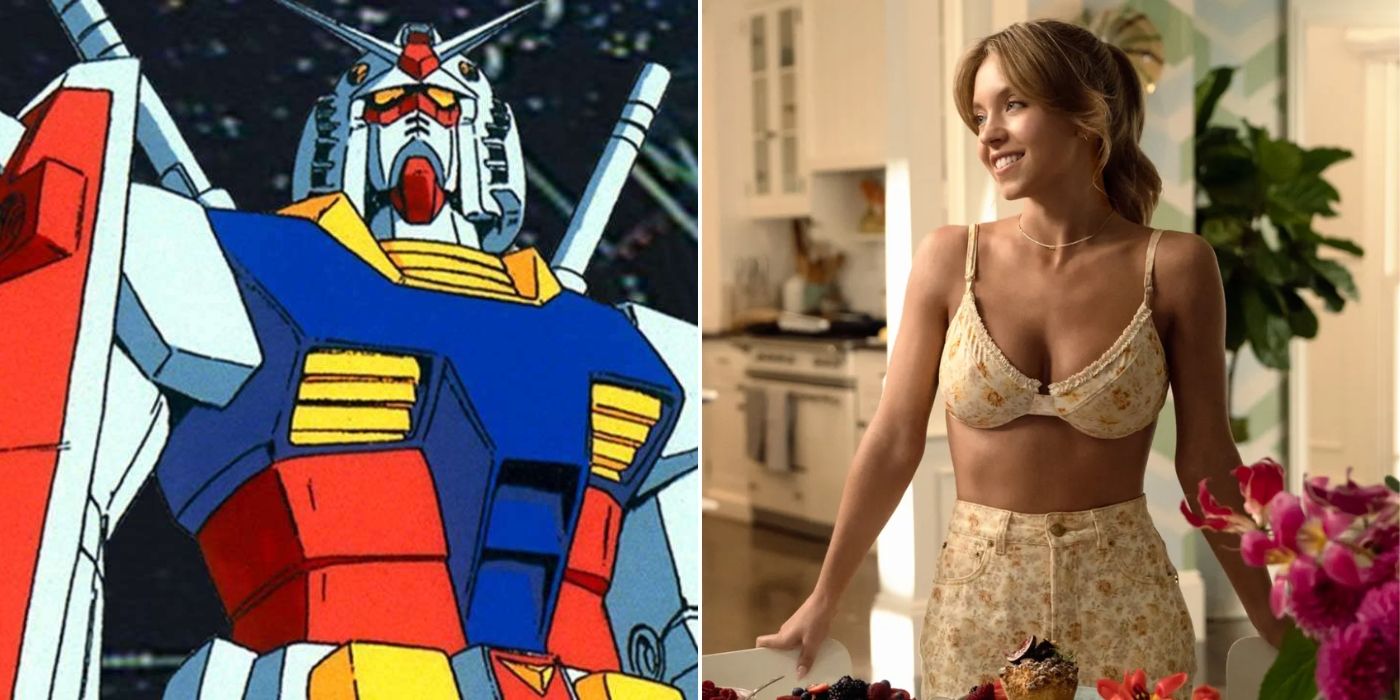

The momentum seemed to continue to gain traction: every season thereafter saw more diverse body types, sizes, and faces on the runway, evidently ushering in an era that promised to be more inclusive. All of this indicated that brands were, finally, prioritizing representation, buoyed by headline-making articles for doing so. Before the pandemic hit, the spring 2020 season had the most plus-size models on the runway, with 86 castings, according to The Fashion Spot’s diversity report. It dipped in the following seasons due to pandemic-related concerns (virtual runways, canceled shows, production issues), but the fall 2022 season saw an uptick, with a new record of 103 plus-size appearances, or 2.34 percent of total castings.

And that’s why the fall 2023 season at NYFW proved to be immensely disappointing — a contrast stark enough for showgoers to sit up and take notice. After so much progress on body inclusivity, it feels like the industry is backsliding.

Precious Lee walks the runway at the Christian Siriano spring 2017 show. Image Source: Film Magic / Peter White

In the weeks before this most recent season, Conor Kennedy, founder of Muse, a model agency that launched its curve division 11 years ago, was convinced that it would be the most body diverse one yet. In fact, for precastings, he says casting directors saw “more curve models of different sizes than I’ve ever seen in my career, and that was very exciting.” But fittings told a different story.

“If the clothes don’t exist, then it doesn’t matter if those casting directors saw [models who are size] 14, 16, 18, 20. I think it comes down to design choices, which are always made well in advance of the runway show,” Kennedy tells POPSUGAR. “These shows are powerful symbols of what is fashion, what is beauty, and what is glamorous. And when you see an absence [of body diversity], it’s a message to not just customers, but to the wider culture, that there is no place for that size. And I think that’s a very unfortunate message to walk away from New York Fashion Week.”

Kennedy says he saw an increase in size 8, 10, 12 models, but a notable drop in size 14, 16, and 18 models. And it’s hard not to see a connection between the lack of body inclusivity on the runway and the recent sudden slimming of Hollywood, along with the meteoric popularity of medications that lead to rapid weight loss — namely Ozempic — and buzzy procedures like buccal fat removal.

“Our society intrinsically still operates around weight bias.”

“The reality is that fashion, like other industries in the arts, is a reflection of social discourse — when social discourse became more inclusive, fashion became more inclusive. Now, we’re seeing the reverse,” says Nadia Boujarwah, cofounder and CEO of Dia & Co., a platform that since its inception in 2015 specializes in styling and providing plus-size clothing (in sizes 10 to 32) from a stable of brands that range from Girlfriend Collective to Carolina Herrera. “In the previous five years, we moved to a healthier dialogue around women’s bodies. And unfortunately, in the past six to nine months, that’s regressed.”

For Boujarwah, so much of that comes down to the content we’re all consuming. “The conversation on social media changed — there’s a focus on this new skinnier body type,” she says. “Our society intrinsically still operates around weight bias, and in some ways, these dynamics have fanned the flames of weight bias in a way that’s allowed this to really explode.”

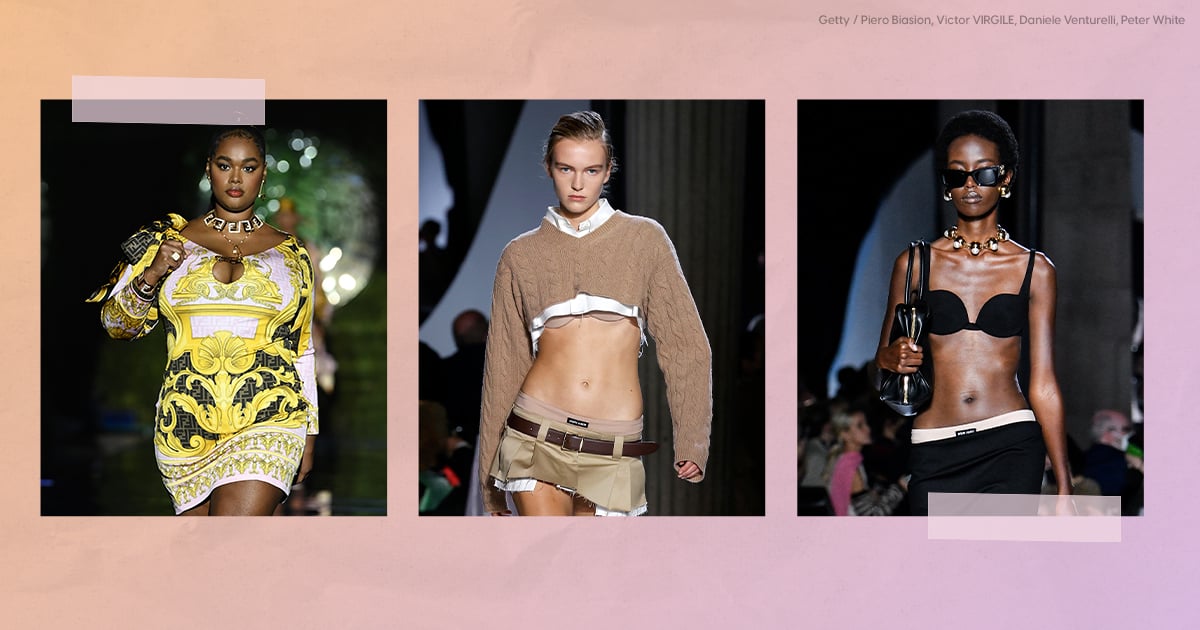

McCall traces it back to the Miu Miu spring 2022 show that sent ripples of shock across the industry — and pop culture writ large — with its parade of ultra-low-rise, micro-mini skirts. It signaled the revival of Y2K fashion, an era that was particularly punishing for women’s bodies, so much so that eating disorders inadvertently became threaded into the zeitgeist.

A model walks during the Miu Miu spring 2022 show at Paris Fashion Week. Image Source: Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images / Victor Virgile

It isn’t quite a reach then that the concern with the return of Y2K fashion is inextricably linked to a very specific body type — and thus, an unhealthy approach to achieving that look. And that was evident this season, with some critics even taking note and calling out the dangers of a very “in” skinny look.

“If we’re mining the Y2K era for inspiration, the body aesthetics of that period might be consciously or subconsciously being emulated as well,” McCall muses. “Some of that is because we do treat body types as trends, and it could be pushback — again, consciously or subconsciously — to the past several seasons of body diversity.”

The repercussions are twofold: unattainable beauty ideals are poised to negatively influence the next generation and how they perceive their own bodies, and a lack of runway representation could detrimentally impact extended sizes offered in retailers, leaving an entire market unseen and underserved.

“Our analysis shows that there’s a two-year lag between the number of plus-size models coming down the runways in New York City and what the average consumer can buy at an everyday retail location,” says Boujarwah. The spring 2020 shows boasted the largest number of curve models, and the number of styles in extended sizes at retailers have gradually increased, peaking to current-day inventory, she adds.

“The runways really are the leading indicator for where the industry is going,” Boujarwah continues. “There’s a lot of responsibility that comes with being at the pinnacle and setting the norms, and that does trickle down to everyday consumers in a more direct way than people realize.”

Boujarwah says she’s heard department stores are already cutting back on plus-size orders in anticipation of demand shifts that may happen in the next couple of years. For her, it’d be “heartbreaking” to see extended sizing backslide because of this past season.

“The push for body diversity is important, but it needs to go hand-in-hand with extended sizing.”

But runway representation is more than just putting more curve models on the runway. For meaningful change to take place, it’s less about meeting a quota and more about overhauling a business, so that it’s inclusive of extended sizing.

“For a while, if a brand cast a plus-size model on the runway, they got a ton of press,” says McCall, recalling when Versace cast Precious Lee in its spring 2021 show. “It was a trend, it was a topic of conversation. But if you’re not thinking about it from a holistic, ‘this is not just representation, but an important demographic we’re not reaching and selling to’ perspective, then it’s not going to work.”

She sums it up like this: “The push for body diversity is important, but it needs to go hand-in-hand with extended sizing in your brand; otherwise, it’s easy to revert back because it’s not part of a structural change.”

It’s no secret there’s money to be made in the plus-size industry — it was valued at $24 billion in 2020 in the US alone, received a global market value of $276 billion in 2022, and is projected to reach $288 billion by 2023. From a cursory glance, it’s good for business for a brand to venture in extended sizing, but it has to be done well. And that takes time (earning the trust of your consumers), investment (sourcing the right patternmakers), and considered execution (launching inclusive marketing and striking deals with the right partners).

“Where the opportunity doesn’t end up materializing for folks is when they think, ‘We can just do a little bit and be successful,’ and that never works. If you’re going to invest a little, you’re going to get a little back,” Boujarwah explains. But some brands are doing it right; Boujarwah counts Tanya Taylor, who has partnered with 11 Honoré and is committed to investing in product and design, and lingerie brand ThirdLove, which has been inclusive from the beginning, as shining examples.

A model poses for a Tanya Taylor presentation during NYFW in 2019. Image Source: Getty Images / Dia Dipasupil

McCall echoes that sentiment, also naming Taylor and Christian Siriano for paving the way. They’ve both proved that it’s possible for luxury brands to embrace extended sizing — and have it pay off.

“[Because of the investment,] I understand why some smaller brands don’t do it, but when you’re a bigger brand and you’re doing custom plus-size designs for actresses and models and you’re still not selling it, then the only reason you’re not selling it is because you don’t want your clothes to be associated with fat people,” she says. “I’d argue about 85 percent of those in the fashion industry don’t care about body diversity. It’s not an issue for them.”

The through-line here is getting people — the designers, the upper echelons of major luxury fashion conglomerates — to care, instead of shrugging their shoulders, digging in their heels, and generally being obstinately resistant to change simply because the industry has operated in a singular way for so long.

Even so, Kennedy is optimistic about change — in New York at least. If wardrobe-undressing, dog-resembling robots can grace the runways at Paris Fashion Week (see: Coperni), surely we should be seeing greater body diversity on catwalks around the world. Sadly, as of now, that’s not the case.

“The reality is that nobody is looking to Europe for that change — New York has always been more dynamic, more progressive in terms of youth and streetwear culture. And we expect more from the market because there’s more freedom to play,” Kennedy says. “So I hope that over the next few seasons, we see emerging and established brands take a chance.”

You can view the original article HERE.

![Tom Hardy & Guy Ritchie’s ‘MobLand’ Crime Drama Lands [X] Rotten Tomatoes Score Tom Hardy & Guy Ritchie’s ‘MobLand’ Crime Drama Lands [X] Rotten Tomatoes Score](https://static1.moviewebimages.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/tom-hardy-in-guy-ritchie-s-mobland.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/04/01/828/n/1922564/9432574867ec361a713285.06370027_.jpg)