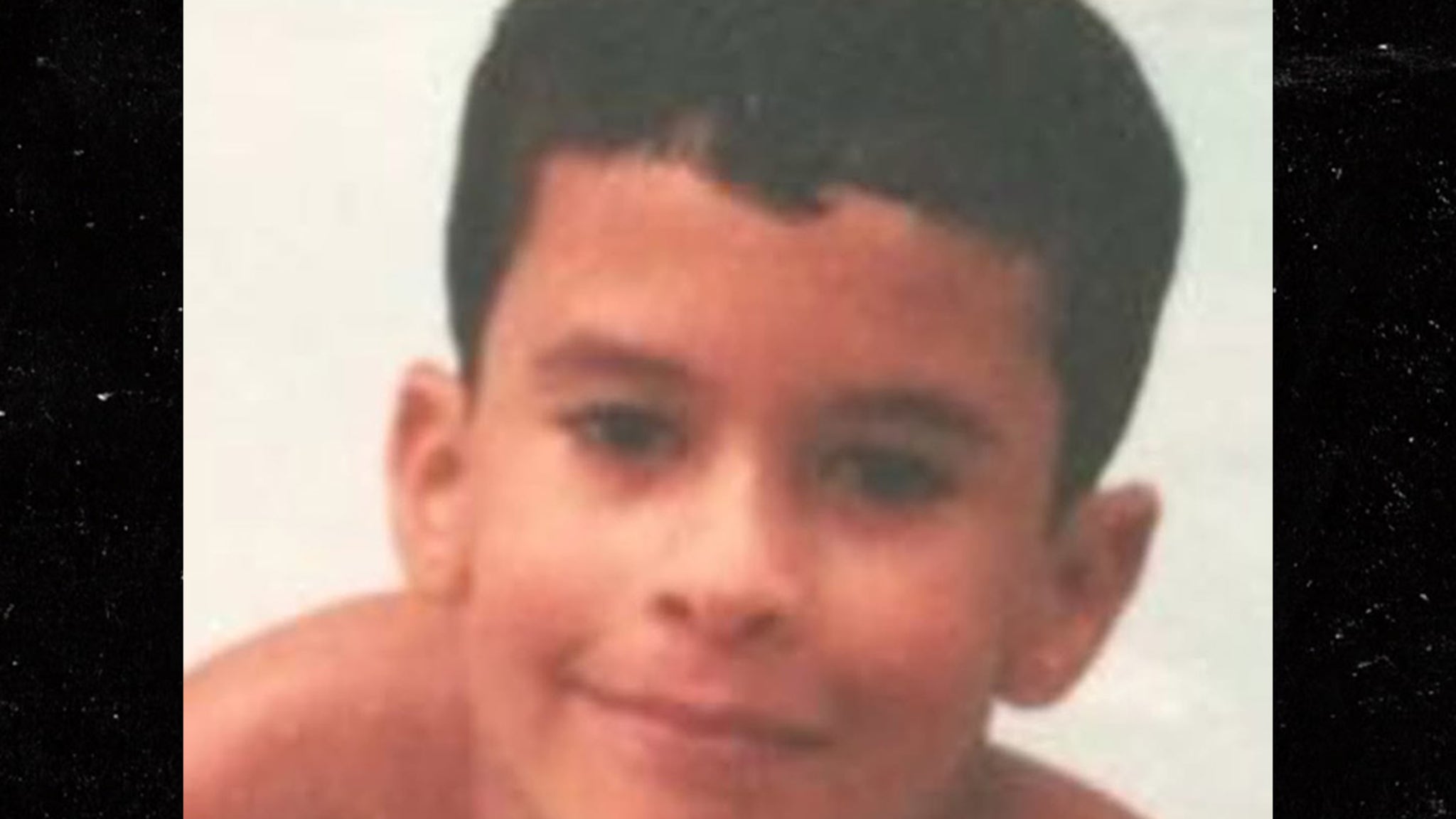

It’s been three decades since Pedro Zamora appeared on MTV’s The Real World: San Francisco, but his impact feels as immediate as ever.

The gay Cuban-American became a pioneer when he openly discussed his HIV-positive status on the reality show in 1994. He passed away from AIDS-related complications in November of that year, hours after the final episode featuring him aired. He was 22.

Today, on National Latino AIDS Awareness Day, Latinx HIV activists continue to educate communities about HIV myths and the importance of getting tested and treated. As they share with Yahoo Entertainment, many draw strength from Zamora’s indomitable spirit, finding in his story both a roadmap and a rallying cry.

The 1990s and the HIV crisis

Since 1981, nearly 39 million people globally have died from AIDS-related illnesses, the result of HIV if left untreated. In the 1980s and ’90s, the height of the epidemic, gay and bisexual men were disproportionately affected by the disease. In fact, AIDS was the leading cause of death in men ages 25 to 44 in 1992.

The rising rates sparked fear, stigma and hysteria among the public, fueling laws and policies that criminalized people with HIV and, more intentionally, queer men. Many of those laws still exist today while others have slowly reformed, like the FDA’s blood ban that eased restrictions on queer men from making life-saving blood donations.

By the mid-1990s, two years after Zamora’s death, advancements in treatment transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic condition. With today’s treatments, many individuals with HIV can expect a lifespan nearing that of those without the virus (albeit with unique health challenges, per the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).

Enter: Pedro Zamora

During this time, when stigma was at its height, Zamora shared several personal life moments with millions of viewers on The Real World, including a commitment ceremony with partner Sean Sasser, one of the first same-sex ceremonies to air on national TV. Throughout the season, his emotional confessions about discovering his status at 17, and how he channeled the shock into activism, inspired many to learn about the virus — and the government’s delay to fund research, prevention and treatment.

The cast of The Real World: San Francisco: (left) Puck Rainey, Rachel Campos, Cory Murphy, Pam Ling, Mohammed Bilal, Pedro Zamora and Judd Winick. (MTV) (Courtesy Everett Collection)

Diversity was a core element of the show, executive producer Jonathan Murray told MTV News in November 2014, which is why it was important for him to include an HIV-positive person in the house.

“When we cast Pedro, we knew he was someone special, but we had no idea the impact he would have on our society, our culture and putting a face on AIDS,” Murray said at the time.

Danny Roberts, who came out publicly on The Real World: New Orleans in 2000, says Zamora sparked a “national conversation” about LGBTQ issues, which created a snowball effect on America’s collective conscience.

“He wasn’t an activist in the way we think of activists today,” Roberts, who was diagnosed with HIV in 2011, tells Yahoo Entertainment. “He was, simply, a human with a giant heart who was open and sharing. He was allowing people to come into his world as an observer, and you couldn’t help but feel anything but empathy.”

Zamora’s candidness was unlike anything seen on TV before, says Jose Zuniga, president of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, who recalls meeting Zamora at the Capitol before his death while the young activist was lobbying for federally-funded sex education in schools.

“I remember him as a brave, tenacious person who wanted to tell his story,” Zuniga shares. “He raised awareness among Congress, the general public and the Latino community not just about HIV issues, but also LGBT concerns, which were exacerbating and fueling new infections.”

It was important for HIV-positive folks to tell their stories at that time, Zuniga explains, stressing that Zamora “humanized the disease for a generation” and “created awareness that we needed to invest in medical infrastructures that ensure [more HIV treatment] drugs are being made available.”

Zamora’s fight for Latino communities

But Zamora was an activist long before appearing on The Real World. In July 1993, he testified before Congress to demand broader sex education in American schools and for Spanish-speaking communities.

“If you want to reach me as a young man — especially a young gay man of color,” he said at the time, “then you need to give me information in a language and vocabulary I can understand and relate to.”

Sean Sasser and Pedro Zamora kiss during their commitment ceremony on MTV’s The Real World: San Francisco in 1994. (MTV)

Tony Morrison, communications director at the LGBTQ media advocacy organization GLAAD, says Zamora “broke stereotypes” for Latinos and gave way for many to have broader discussions about the shared challenges they face in health care, queer issues and beyond.

“By standing up and saying, ‘This is my story,’ he inspired countless [others] to do the same,” Morrison, who came out publicly about his HIV status in 2021, says. “His grit, his humility and joy, despite difficult cards dealt to him in life, will be his lasting legacy.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hispanic Americans accounted for 29% of new HIV infections in 2021, despite making up 18% of the total U.S. population. Yet, they experience unique barriers in sex and HIV education, including cultural stigma, economic disparities and language barriers, to name a few. Addressing them requires multifaceted strategies that consider these challenges, notes Morrison.

That’s the same message Zamora was trying to get across nearly 30 years ago.

“Raising visibility and acceptance of these communities is part of the solution, as is taking action against ongoing threats to everyone’s health, safety and freedoms,” says Morrison. “We all have the power and ability to drive change and shift culture just by sharing our own stories.”

Such stories are paramount for change, adds Zuniga.

“There aren’t as many people speaking their truths. We need more of that, not only from people living with HIV, but those who are affected by it,” he says. “Pedro was trying to address this very clearly through The Real World and his advocacy. And we need more.”

Pedro continues to inspire HIV storytellers

Erick A. Velasco, creator of The Homo Homie Podcast, which discusses HIV stigma in Latinx communities, says Zamora inspired him to reclaim his own story by turning shame into action.

“Being able to have Pedro as a reference now to look back upon, and with him being Latino, truly helped the way I do things with my life today,” Velasco tells Yahoo Entertainment. “I relate with Pedro’s story: family struggles, poverty, dealing with sick parents, being gay and navigating the way we live with HIV. It’s a way for me to know that, like him, I’m doing the right things too.”

Other HIV storytellers say Zamora’s life is a testament on how art can be a vessel to destigmatize the virus. But more work needs to be done.

“I was 13 years old when I first watched Pedro on The Real World. It was only about four years after that I lost my uncle to AIDS in the same city where Pedro lived,” says Sarah Hall, showrunner at Harley & Co. and producer of the Cannes-nominated series Love in Gravity, which highlights HIV in the Latinx community.

“Looking back,” she continues, “Pedro’s bravery and visibility should have been just a beginning — almost 30 years later, stories about characters living with HIV and stories about HIV prevention in entertainment should be common — but they aren’t.”

Charles Sanchez, an HIV-positive cabaret performer in New York City, speaks openly about his status at performances as a way to educate and entertain. He says Zamora’s life is proof that there’s power in vulnerability.

“I find him more inspiring now,” he tells Yahoo Entertainment. “For people living with HIV, he said, ‘Hey, you can live. You can have a wonderful life as long as you can.’ That was important.

“We need Pedro’s legacy to ring out strong and loud,” he continues, “to remind us to talk to each other, to communicate with each other and to take care of each other.”

You can view the original article HERE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/07/25/018/n/1922398/ccfe7e9c64c05a4249fc77.46211983_.jpg)