If buildings are haunted, then the Chelsea Hotel would be heaven for creative ghosts. The Chelsea has housed some of the best artistic minds of the past century, with a proverbial guest book thicker than the Bible. Dylan Thomas, Mark Twain, Jack Kerouac, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Madonna, Andy Warhol, Stanley Kubrick, and countless others stayed in its New York rooms; Nancy Spungen was found stabbed here (as depicted in the punk rock movie Sid & Nancy) and Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyysey here. It’s built for legends.

Filmmakers Maya Duverdier and Amílie Van Elmbt stumbled across the Chelsea at a transitional moment in its existence when it was far from the regal, hip Mecca for artists it had once been. Under new ownership in 2011, the building was gutted, its artworks taken down, and no new reservations were accepted as extensive renovations began, which would last nearly a decade. With its walls down and insides torn apart, Duverdier and Van Elmbt began chronicling the remaining tenants, their camera gliding through the building like a ghost itself. The result of this was Dreaming Walls: Inside the Chelsea Hotel, a beautiful meditation on aging and art, capturing an iconic part of New York City (which is partly why the director Martin Scorsese serves as executive producer).

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

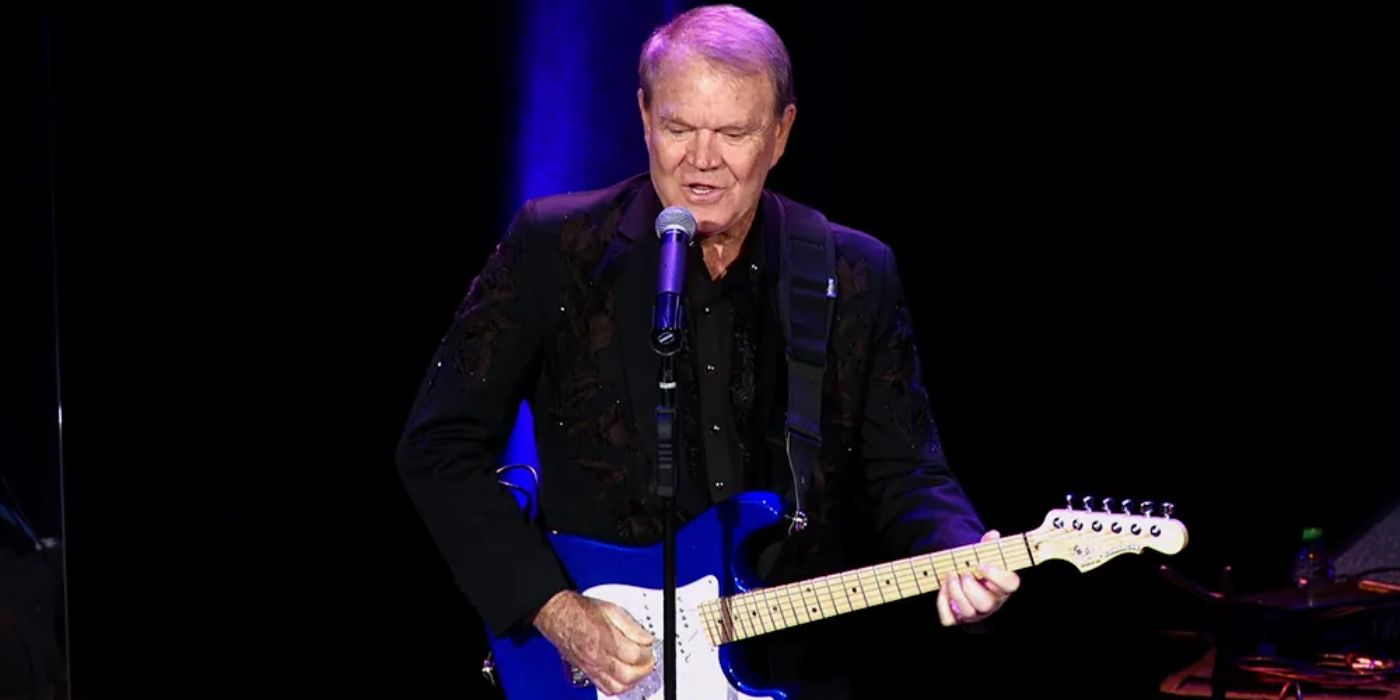

Maya Duverdier and Amílie Van Elmbt Film the Dreaming Walls

Magnolia Pictures

Van Elmbt had worked in fictional narrative films (and was at a screening for her movie The Elephant and the Butterfly when she happened upon the Chelsea), and Duverdier had dabbled in documentary. Dreaming Walls: Inside the Chelsea Hotel blurs the lines between the two forms in a hybrid documentary kind of way, though Van Elmbt doesn’t see the difference between the two. “I don’t make boundaries between fiction film and documentaries,” she tells MovieWeb, “it’s the same thing, it’s just a different approach. That’s also why we wanted to give this kind of cinematographic look to the film and not be like the classic American documentary where people are sat and just talk.”

As such, Dreaming Walls is not didactic; the film lacks the type of exposition one would find in documentaries that use voiceover narration or onscreen text. Instead, Dreaming Walls is poetic and patient, filming the building and tenants in an appropriately dreamy way, interviewing people with remarkable intimacy, and incorporating archival footage. The kind of camera and lighting that is used beautifies the place with a softness and warmth, rather than documenting the grit and gristle of an ugly construction site. Perhaps the most brilliant visual decision was to project some of that archival material onto the actual walls of the building so that its past tenants and history flicker across some of its decrepit decor and crumbling architecture. It’s a perfect choice that brings the title to life and manifests the idea of being haunted.

Magnolia Pictures

While Duverdier and Van Elmbt are hardly ghost hunters, ghosts are mentioned; a construction worker talks to a tenant about feeling their presence, plastic sheets strewn around him as the elderly tenant leans in eagerly over her walker. Mostly, though, the idea of ghosts and hauntings is a metaphorical or emotional one. If any building can have a haunted atmosphere, accrued over generations, built by myths and legends, it would be the Chelsea Hotel.

Related: Best Films Set in New York, Ranked

Famed author Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, Marilyn Monroe’s ex) wrote a story about the hotel, The Chelsea Affect, which describes this. “The Chelsea, whatever else it was, was a house of infinite toleration,” Miller writes, with “an operating chaos which at the same time could be home to people who were not crazy […] The place, in fact, reminded me of Nevada in the early Sixties and still does. There was a similar kind of misfittedness about so many of the people who had either dropped out or never entered the normal ruts where most human traffic flows.”

The Tenants of the Chelsea Hotel

Magnolia Pictures

The Chelsea Hotel attracted wild-eyed dreamers, but like much of New York, was turning into a place where only rich people could afford to dream. So the filmmakers wanted to document the dying days of these last dreamers. “The situation at that very moment in time in the Chelsea Hotel was so crazy,” Van Elmbt says. “Those people that were living there next to the jackhammers were a bit in danger, and we felt like their memory, their existence will be erased by the new place that will be a luxury hotel filled with wealthy people. So we felt like our job was to pay tribute to the people who used to dream in this place, so it was much more like kind of a duty, we felt that doing this thing was super important.”

“If we had wanted to invent such great characters,” Duverdier says, “we could have never done so, because sometimes reality is bigger than fiction. It was them that we wanted to film, it was really these people that touched us.” Dreaming Walls hovers around the building, listening to its tenants, sometimes occupying their very residences and simply observing them.

Arguably the most charismatic person in the film is the dancer and choreographer Merle Lister, who wanders the floors of the Chelsea taking notes and conversing with young construction workers as she pushes along her walker. She’s almost hypnotic sometimes, like when she does a dazed octogenarian dance in the hallways or the moment she dances the mambo with one of the construction workers.

Magnolia Pictures

Lister has her portrait done by Skye Ferrante, one of the artists living in the Chelsea, and Ferrante also captures the camera’s gaze whenever he’s onscreen. He tenderly constructs these small, meticulous sculptures made out of wire, and narrates scenes throughout the hotel with his own dreamlike writing. A simple scene where he and his daughter share breakfast on the couch in his apartment is entrancing and representative of the slightly surreal but nonetheless slice-of-life moments which make up Dreaming Walls; Inside the Chelsea Hotel.

Dreaming Walls Documents Age With Respect

Magnolia Pictures

Most of the people in Dreaming Walls were older, long-time tenants who didn’t want to leave during the renovations, and Duverdier and Van Elmbt had almost unfettered access to them, having to edit down 150 hours of footage with them into a feature-length film. What’s often remarkable about Dreaming Walls is that it’s able to capture this melancholic feeling of getting older where something in its twilight years (buildings, cities, people) approaches the end of its time, but the film is never grim or exploitative about it. It depicts aging and the death of an era (of art and life) with respect and warmth.

Related: 8 Movies About Painters That Are Visually Stunning

“We could have done like a completely different thing, because they had very open hearts and sometimes, you know, they were not at their best,” Van Elmbt says. “It was super important to really portray them the best we could, and to be true to what they were willing to share and not to just take what we wanted and do our editing to make them look like freaks, you know […] The way you want to put your gaze on people, especially when you are dealing with reality and crazy situations, it is so important to have a respectful eye.”

Magnolia Pictures

Without explicitly saying anything through exposition, Dreaming Walls depicts massive changes in culture and economics. Though it feels like a tone poem about aging, it’s impossible to ignore some subtext about what the world is aging into. As New York turns from a haven for artists into a massive extension of Wall Street, with exorbitant rent prices pushing out anyone but the wealthy, the luxury remodeling of the Chelsea Hotel becomes a stand-in for larger social issues like income inequality and the housing crisis. As the wild brilliance of art in the 20th century fades into the more blandly commercial or expensively elitist art of the 21st century, the hotel seems like a metaphor for the death of bohemian culture. Miller writes in The Chelsea Affect:

The Chelsea in the sixties seemed to combine two atmospheres: a scary and optimistic chaos which predicted the hip future, and at the same time the feel of a massive, old-fashioned, sheltering family […] There is an indescribably homelike atmosphere which at the same time lacks a certain credibility. It is some kind of fictional place, I used to think. As in dreams things are out front that are concealed in other hotels, like the wooden bins in the corridors in which the garbage pails are kept, and for some unknowable reason this sort of candor seems so right that you smile whenever you pass the bins. It may simply be that nobody is urgently concerned about what is happening because nobody quite knows what is happening, or maybe there is a kind of freedom or severe disconnect with plain reality, or, as the saying goes, a sense that the inmates have long since taken over the asylum.

With the luxury hotel reopening this year for wealthy clients, it seems as if the asylum has taken back control. Fortunately, there is Dreaming Walls to remember what it was like before it passed away. From Magnolia Pictures, Dreaming Walls: Inside the Chelsea Hotel is released July 8th in select theaters and On Demand.

You can view the original article HERE.