Animation is often at its best when delivering what can only be possible within its medium, creating worlds and images which are otherwise unthinkable in live-action films or literature. From the dancing brooms of Fantasia to the eyeballed lumps of adorable coal in Spirited Away, animation has the ability to express a creative vision with more imagination than almost anything else. Paradoxically, this is what makes Mamoru Hosoda’s new film Belle be simultaneously wonderful and, in some minor ways, a missed opportunity.

This Japanese anime film concerns a world where virtual reality has really taken off, to the extent that five billion people are members of a digital platform simply deemed ‘U.’ “You can live as another you,” goes the tagline to the social media-like app. “You can start a new life. You can change the world.” The question is, though, which “you,” which “life,” and which “world?”

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

The film isn’t exactly dystopian about any of this, though. Unlike movies such as Ready Player One, eXistenZ, or The Matrix, the world of Belle seems to have essentially handled such technological advancements the way that humanity has handled YouTube or Instagram– it may be “ripping apart the social fabric of how society works,” as the former VP of Facebook has said, but it’s also mind-numbingly pleasant on occasion, along with being a largely banal distraction. If it’s the demise of society, it’s a slow and mediocre one, with lots of cat videos and predictable selfies as its death throes.

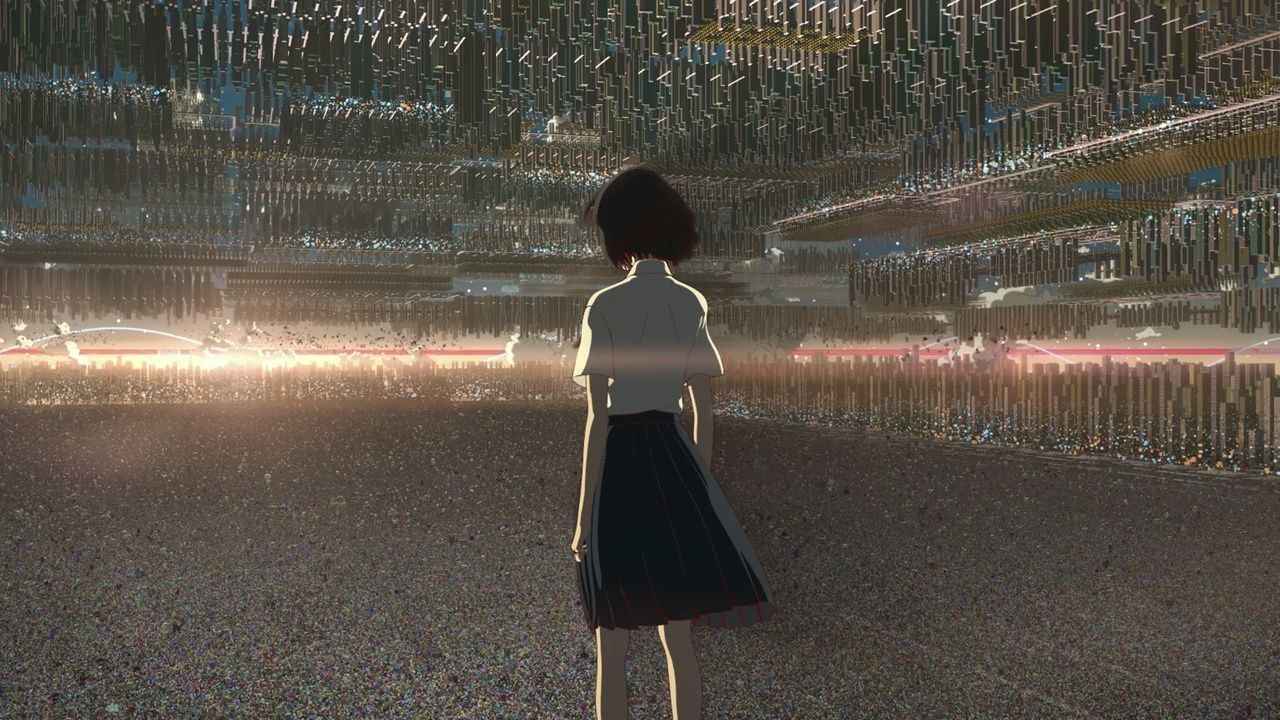

The five billion people of U fly around megacities that look like microchips, gathering in cliques and commenting to each other the same way that 510,000 comments are posted on Facebook every 60 seconds. Biometric readings from ear-pods and algorithmic collections of internet histories and photographs coalesce to help create a person’s avatar, and the virtual world is filled with all sorts of strange and imaginatively designed creatures. The avatars seem to be the biggest appeal of U, what with their ability to recreate a person entirely and give them a new life online.

Toho

This is exactly what Suzu, the protagonist, needs after her mother dies while heroically attempting to save a child in danger. Suzu was extremely close with her mother, who inspired a love of music and singing in her. After this tragedy, the trauma remains so acute that Suzu literally vomits whenever she tries to sing. She hardly eats, and her relationship with her father is largely monosyllabic. She is terrified to talk about her feelings with anyone, sometimes including her only real friend, Hiroka. She’s essentially a ghost because that’s what ghosts are– not the people who die, but everyone who is left behind, haunted by the absence of who has passed and forced to live without them.

Related: Belle Trailer Announces Mamoru Hosoda’s Anime Epic is Coming to U.S. Theaters This Januar

When she discovers U and the possibility of changing her identity, Suzu embraces the anonymity of the platform to tap into her musical potential once again, becoming the titular Belle. There is no direct correlation between U and the real world; nobody knows the actual identity of anyone in the virtual sphere unless someone is ‘unveiled’ for serious reasons and automatically banned from the platform. This tabula rasa allows Suzu to unleash the beautiful, confident musician who dwells within her (but who has been caged by grief) onto U’s canvas. Her voice and persona, like anything online, gather mixed responses, but she quickly develops a following of lovers and haters which grows exponentially into the millions, making her the most famous singer in the alternate universe.

The remainder of the film is a variation on the classic Beauty and the Beast narrative, as a disruptive, aggressive dragon-like character is hunted down by the guardians of U for breaking numerous rules, and Belle sees some sort of beauty in him and attempts to save him from both the public and himself. This formula can be inherently toxic– the original 18th-century fairy tale from Madame de Villeneuve has not aged well and, in a sense, neither have the Disney iterations of the tale. The traditional story essentially propagates a destructive and misogynistic trope, wherein a woman is told to endure the emotional and physical violence of a domineering male (who kidnaps her and holds her prisoner). The woman believes that she can ‘fix him,’ and that beneath all of his insults and screaming, he is actually a beautiful soul; the luxurious palace where he keeps her captive probably helps. In the fairy tale, when Beauty learns of Beast’s death, she weeps and laments how she should have loved him more. When she cries out, “I am sorry! This is all my fault,” the Beast suddenly awakens and is transformed into a prince. Gross.

Toho

Thankfully, Hosoda’s Belle deconstructs the traditional fairy tale in a less chauvinistic vein, though he retains the Disney style of sudden song-bursts. The writer-director does not make Suzu (and her alter-ego, Belle) a victim; she isn’t kidnaped, she doesn’t need to be rescued, and she isn’t responsible for anyone’s destructive behavior. Her relationship with the Beast isn’t even a romantic one, technically. Her romance lies outside U, in extremely awkward, real-life moments. Instead, the Beast embodies the old adage that ‘hurt people hurt people,’ and the film ties his behavior to online bullying and the bevy of internet comments which can also shame and dismiss people.

Related: Explained: Avatar the Last Airbender & the Success of Western Anime

Suzu begins a sometimes humorous, sometimes heartbreaking quest to track down the Beast before the forces of U do, believing that he has goodness in him. What she discovers is truly sad, but extremely appropriate for a film about society’s desperate need to escape from various traumas and find some version of reality that lacks all these griefs, sorrows, and fears. The lyrics of her songs throughout the film reflect this well, helped by the fact that the pop music (including the epic, emotional closer) is often very good.

While some of this is heavy, the majority of the film and the search for the real Beast is light and breezy. Hosoda draws from a variety of technological ideas to tell his Belle, creating extremely busy frames brimming with social media comments, internet tabs, and online video chats during the search. He uses a kind of Greek chorus of internet comments throughout the film in a humorous and satirical way, along with screens upon screens of internet windows, video chats, text messages, and so on. Whenever technology is involved like this, the animation practically explodes with wild, busy chaos, an energy-addled fever dream of epic digital proportions which probably reflects the minds of young people who have grown up using this technology.

The animation throughout the whole film is gorgeous, worthy of the heartwarming 14-minute standing ovation the film received at the Cannes Film Festival. The vibrant and colorful world of U is compared to the more tonally subdued and calm two-dimensional animation of reality, of a world where parents die, kids are bullied, and social anxiety runs rampant. The offline world may be a stark contrast to the online one, but it has a kind of calm realism to it that’s extremely effective. No scene better captures this than an extended, uncomfortably funny sequence in which three of the young characters try to express their actual feelings. The frame stays the same, focusing on a dull and empty train station, and the film doesn’t cut for what seems like an interminably long time. The characters stumble in and out of frame, blushing and having the hardest time actually being honest about their emotions. It’s funny, awkward, adorable, and sad all at once, and perfectly depicts the kind of clumsy, complicated reality which so many kids flee from and toward online alternatives.

Toho

This is a film that is stuffed with thematic ideas– bullying, viral sensations, social anxiety, PTSD, and virtual reality are all explored in-depth, making the ideas of the movie as busy and frenetic as some of its animation. Belle is deeply interested in the digital age, so it’s all the more surprising, then, that the movie doesn’t take full advantage of its fascinating concept and incredible animation to really delve into U. The visual creativity of its online sequences is often stunning (pop stars ride whales fitted with stereo equipment through the air, for instance), so it’s a shame that the world it creates often seems underdeveloped with so much untapped potential. U essentially feels like a plot device for Suzu to heal her trauma and for the film’s narrative to progress, never really feeling like a fully fleshed-out digital space.

Regardless, the movie is beautiful and heartwarming. Portions of it (especially the music) may be too sentimental for some, but anime fans should enjoy it immensely, along with anyone interested in deconstructing the Beauty and the Beast mythos. It is a sweet, buoyant film that also isn’t afraid of being heavy and emotionally serious in its coming-of-age tale. Hosoda was nominated for the Best Animated Film Oscar recently for his excellent Mirai, and is sure to receive another nomination for this beauty.

The Witcher Is Getting Another Anime Movie After Nightmare of the Wolf Success

Read Next

About The Author

Matthew Mahler

(36 Articles Published)

Editor and writer for Movieweb.com. Lover of film, philosophy, and theology. Amateur human. Contact him at matthew.m@movieweb.com

You can view the original article HERE.