I’ve always been fascinated by Roger Ebert’s review of a usually derided film, Paul Schrader’s Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist (recut into the inferior The Exorcist: The Beginning for mainstream audiences). It’s strange to see such a lauded writer (Taxi Driver) and director (American Gigolo) take on the fifth entry in a horror franchise, but Schrader made the best Exorcist film since the original for a simple reason that Ebert nails. The critic says his film, “Does something risky and daring in this time of jaded horror movies: It takes evil seriously.” Dominion comes to mind after seeing the new horror drama Here After, and for good reason.

Evert continues in his review of Dominion: “There really are dark satanic forces in the Schrader version, which takes a priest forever scarred by the Holocaust and asks if he can ever again believe in the grace of God… It also has spiritual weight and texture, boldly confronting the possibility that Satan may be active in the world.” This is also what makes Here After so significant and compelling — here is a film that treats its supernatural subject seriously, both theologically and emotionally. This is a movie that fully commits to the religious register, and that specificity makes its universal themes of guilt and forgiveness more powerful. In a sense, it is a Catholic variation on Schrader’s Calvinist approach.

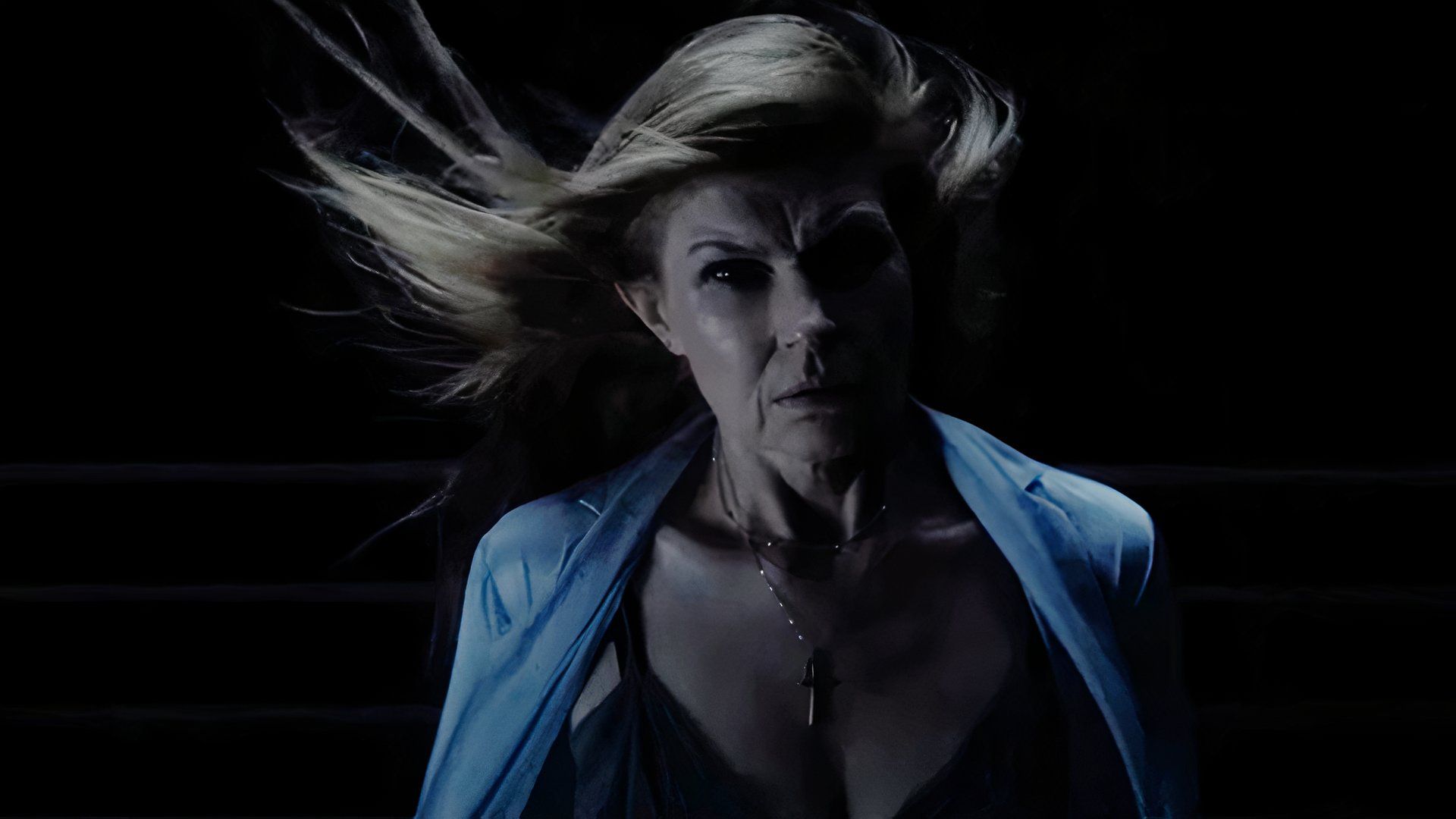

Enough of my diatribe, though — Here After is a powerful little movie that takes its subject deeply seriously and greatly benefits as a result. Connie Britton is phenomenal as Claire, a lonely American woman in Rome who is doing her best to create a great future for her daughter. Both women are deeply scarred by a mysterious event in their past, and when Claire’s daughter miraculously recovers from a near-death experience, those scars seem to manifest themselves in frightening ways. Here After isn’t perfect but, like Dominion, it’s unforgettable because of just how committed the movie is to its spiritual subject.

A Woman Gets Her Daughter Back — Or Does She?

Something happened years ago to Claire and her daughter, Robin (Freya Hannan-Mills), something that lurks beneath the surface of Here After, something which contributed to Claire’s divorce from Robin’s Italian father, and led to Robin’s language issues. She isn’t biologically deaf or mute, but she stopped talking early in life and never recovered; she uses ASL and silently masters the piano, hoping to become a great musician. Claire and Robin are very close; they live together, and Claire is a teacher at Robin’s school. They’re survivors barely bound by the past.

When Robin suffers an awful accident, it appears that she’s headed toward heaven. The time that she’s medically dead gets longer and longer as Claire clutches her rosary beads in the hospital’s small church, praying feverishly to the large crucifix on the wall. Religion has been a source of solace for Claire, and it seems to bring her mercy here — Robin not only recovers (and without brain damage), but she regains her ability to speak. Praise the Lord.

Soon, though, it appears that the spirit which came back from the hereafter is darker, crueler, and stranger than the Robin that her parents know. She loses interest in school and playing the piano; she gets paler and paler, and says awful things; she gets obsessive over dead or dying birds. Claire turned to religion to save Robin, and she does the same to confront the girl’s creepy nature. Is an exorcism warranted? Can a priest help? Can prayer?

A Great Connie Britton & Brilliant Catholic Iconography

What ends up actually happening in Here After is better left unspoiled, but suffice it to say, the only way out is through. Claire joins a fascinating local group of people who have suffered near-death experiences or know someone who has, and develops an intellectual relationship with its leader, Dr. Ben (a soulful Tommaso Basili). This finally gives Claire (and Connie Britton, and the film) an open dialogue, and leads to some interesting thoughts after a first act that somewhat drags.

Here After gets better and better the more that Claire’s past is unveiled, and the deeper the film gets into its spiritual exploration. Catholic iconography and symbolic details connect the dots throughout, with the film incorporating baptismal imagery, ideas of stigmata and crucifixion, Catholic notions of repression and guilt, and deeply spiritual themes of suffering and forgiveness. By the end, Connie Britton completely convinces you that this is not just a life and death issue, but an afterlife one as well.

Robert Salerno Guides Here After to a Profoundly Emotional Ending

Director Robert Salerno does an incredible job in his debut feature film, guiding his meaningful motifs, beautiful Roman imagery (from cinematographer Bartosz Nalazek), and intense score (a perfect piece from Fabrizio Mancinelli) to a showstopping ending that will take your breath away and maybe unleash some tears.

Like Dominion and Paul Schrader, Here After may seem like a peculiar film for Salerno. He’s a producer who has worked with incredible directors on some of the best films of the past 25 years — 21 Grams, A Single Man, We Need to Talk About Kevin, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, Smile. A small genre film with an almost entirely Italian cast and crew seems a little ‘beyond’ Salerno, and yet he brings enough passion and curiosity to the project that, with Britton’s great performance (and Sarah Conradt’s well-structured script), Here After becomes one of the best ‘horror’ movies of the year. Here After will be in select theaters and on Digital September 13th.

You can view the original article HERE.