Richard Linklater is a master of nostalgia. In an age of nostalgic television and reboots, Linklater stands out as someone who actually knows how to do nostalgia in an artistic way, rather than as a cheap ploy for financial success. Thanks to the director’s obsession with the passage of time, his films Dazed and Confused and Everybody Wants Some!! are masterpieces of nostalgia, while his Before Sunrise trilogy and 12-year-long Boyhood remain some of the best cinematic experiments about how time changes people.

Now, the writer-director has made his first Netflix movie, the breezy Apollo 10½, a film completely drenched in nostalgia, to the extent that it almost seems like a documentary about the sixties. The semi-autobiographical movie tells the story of young Stanley (voiced by Milo Coy), a boy in Houston, Texas circa 1969, with a family partially employed by NASA. Jack Black wistfully narrates the film as an adult Stanley, in a way very reminiscent of A Christmas Story, describing the boy’s youth in the days before humanity first landed on the moon.

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

Animating a Space Age Childhood in Apollo 10½

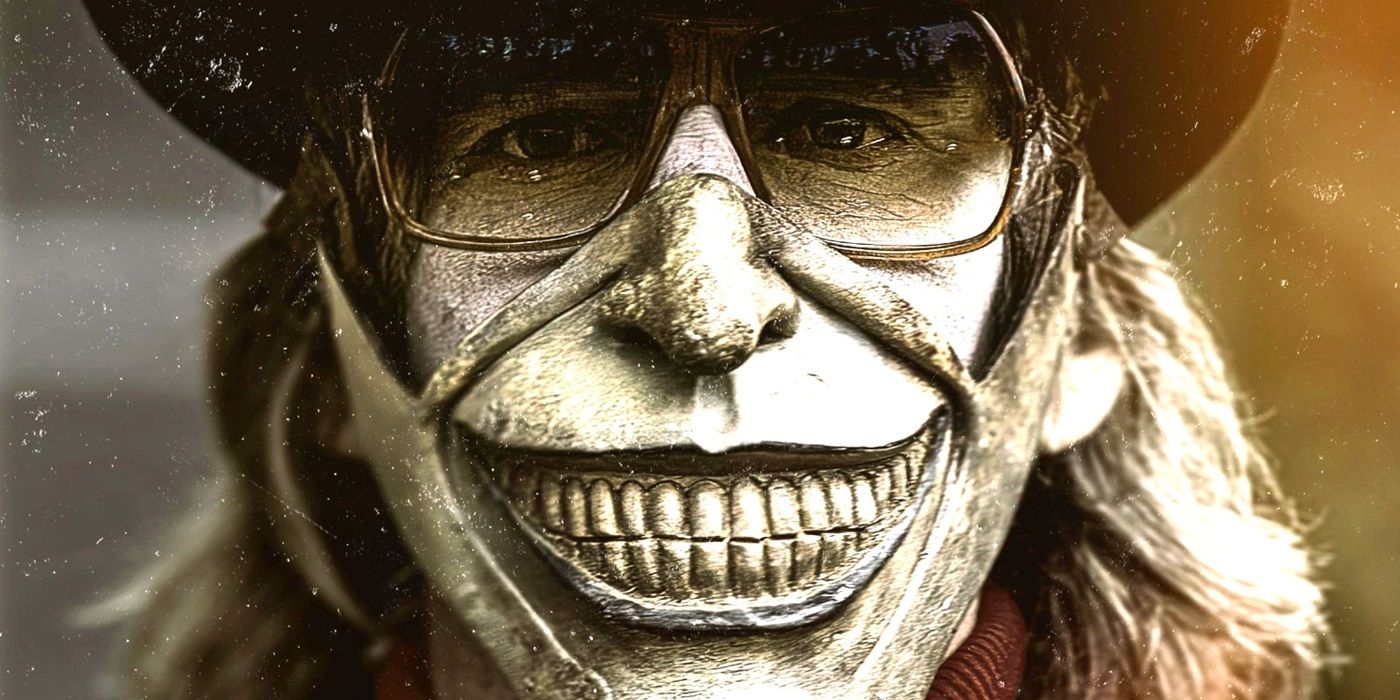

Apollo 10½ is animated in a style that Linklater loves, rotoscoping, in which live actors work against a green screen backdrop and are animated over in post-production. His films A Scanner Darkly, one of the best Philip K. Dick adaptations, and Waking Life, a philosophical masterpiece, utilize this style because it allows filmmakers to be realistic enough, while creating room for some unique visual experimentation that would be otherwise difficult or impossible with live-action. Recently, the Amazon Prime series Undone has used this approach to great effect.

Linklater’s new film, however, is oddly missing the visually fantastical touches which makes rotoscoping such a fascinating alternative to standard animation. In A Scanner Darkly, Linklater could turn Robert Downey Jr. into a giant cockroach or cover Keanu Reeves with an iridescent, shape-shifting suit; in Waking Life, he made characters randomly float, set themselves on fire, or vanish into clouds. In Apollo 10½, there are no similarly surreal or absurdist touches, aside from allowing his young protagonist to imagine himself as an astronaut, chosen by NASA to fly the titular, imaginary Apollo 10½ after an engineering malfunction created too small a rocket.

Related: Netflix Drops Trailer for Richard Linklater’s Animated Film Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood

The rotoscoping probably keeps the budget down, as opposed to filming actual blast-offs and the interiors of space shuttles, but beyond this, it’s a surprisingly straightforward technique. Nonetheless, the animation is likely important s a visual facsimile of the unreliability of memory and nostalgia. Instead of creating a crystal-clear live-action film about 1969, Linklater directs a vibrating, colorful, artificially animated world to better capture the feeling of looking back on the coming-of-age process, which is essentially what Jack Black’s narrator is doing.

Richard Linklater and Nostalgia

Netflix

“You know how memory works.” Stanley’s mother says, “even if he was asleep, he’ll someday think he saw it all.” As such, the film blurs its own lines and draws outside the box, revealing the falsities and fanciful imagination of so-called memory. Thus, Linklater’s look back at 1969 is colored by the realization that nostalgia itself may be illusory, an animated dream world we all make up together. This also creates some incredible rotoscoping of classic news reports, movies, and television moments, which almost come more alive with this animation technique than they do as archival footage.

Regardless, literally half of Apollo 10½ is a documentary-like jumble of nostalgia about 1969. For roughly 40 minutes, the movie takes audiences on a historical whirlwind of a time when one could legally drink and drive – walking on recently invented AstroTurf, playing songs with brand-new push-button phones, practicing ‘duck and cover’ scenarios in the Cold War, watching awful footage of the Vietnam War on television, and turning off that television when TV stations ran the National Anthem at midnight and shut down their broadcasts.

Netflix

This first half of the film is truly bizarre. It initially seems to never let up, a self-indulgent game of ‘Do You Remember?’ that would almost belong better in a VH1 special about the 1960s than it would in a movie, but it somehow becomes mesmerizing as the drawn-out sequences go on for a while. Not only is Linklater detailing the ’60s in a supremely personal and unique way, he’s also using it as a means for character development, fleshing out the central family with the assistance of historical context.

In doing so, he fashions as detailed and beautiful a description of the ’60s (and its end) as has ever been put to film. In terms of narrative filmmaking, it’s completely aimless and largely ‘pointless’ (whatever that even means in art), but it helps create a meticulously exact portrait of Stanley and, as a result, Linklater.

Apollo 10½ and Coming of Age in 1969

Netflix

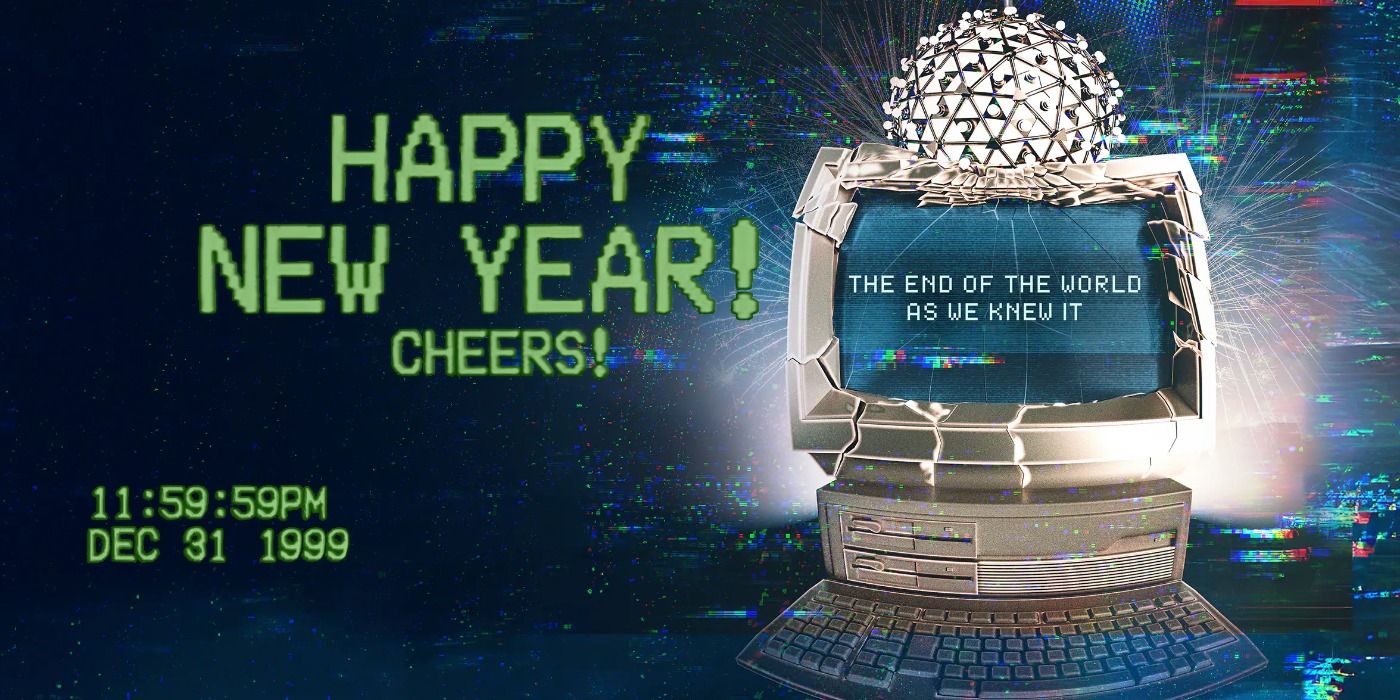

With Apollo 10½, this animated period of time seems beyond magical. As every year passes, the sixties feels more and more like an impossible dream. It’s difficult to imagine how it felt, on the cusp of not just the ’70s but a huge, incredible future where anything seemed possible. As Stanley’s older self says, “The future was so cool and optimistic. It was easy to be swept up in the promise of the future and the thought that science and technology would ultimately fix almost everything. At the top of the heap, the embodiment of all these positive feelings was NASA, and of course the astronauts themselves.”

Related: What Is Apollo 10½? Richard Linklater Shares Details Behind New Netflix Animated Movie

NASA, the space race, and the moon landing became the embodiment of hope, optimism, and humanity’s future, with 600 million people watching the first man walk on the moon and cheering along. It’s difficult to imagine now, with out-of-touch billionaires like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos racking up frequent flyer miles as they pay their way to space, but there was a time when teachers would wheel in a TV to the classroom, and the students would count down each new NASA launch until blast off. There was an unbridled sense of optimism, a positivity that science and technology, combined with the human spirit, might just make everything okay.

This feeling is impossible to replicate today. Between fears over artificial intelligence, the threat of a looming climate catastrophe, the paranoia of high-tech government surveillance, and the monopolies of giant technology companies, science and technology aren’t exactly embraced with open arms, and someone walking on the moon is as blasé and banal as yet another presidential gaffe. Instead, there is much more nihilism in movies about technology and space than there is hope. Perhaps reality and the passage of time aren’t conducive to optimism, and actuality kills hope. Either way, Apollo 10½ beautifully captures a short-lived feeling where anything felt possible, and the future seemed limitless and free.

Netflix

These are, of course, perfect themes for a coming-of-age movie. Taking place between Apollo 10 (in which the moon was orbited) and Apollo 11 (in which man met moon), Apollo 10½ revels in that transitional stage between total innocence (1969?) and the jaded life of teenagers (2022?). Linklater’s little avatar, Stanley, imagines himself as becoming a part of the NASA moon shot, and in a sense, he is; he is part of that generation which gets to grow up in a time when humanity has first walked on the moon. His imaginary NASA scenario, however, also serves as an apt metaphor for the transition into a more cynical adulthood, while shedding light on Linklater himself as a writer and director.

This is undoubtedly the most personal film Linklater has made. The Houstonian has redefined what an independent film is in America, intellectualized the romantic drama, perfected the nostalgic period piece, mastered the philosophical mind-melt, and won acclaim for the coming-of-age drama, but has never really bared his personal heart and soul in a film. His mind has been on display for three decades, but his heart beats anew in Apollo 10½, a touching, beautifully animated, often bizarre and aimless document of 1969 and his childhood. Lovers of NASA, children of ’69, Linklater fans, and anyone looking to transcend the same old nostalgia would do well to check out this aimless but delightful little time capsule.

These are Richard Linklater’s Best Films

Read Next

About The Author

Matthew Mahler

(80 Articles Published)

Editor and writer for Movieweb.com. Lover of film, philosophy, and theology. Amateur human. Contact him at matthew.m@movieweb.com

You can view the original article HERE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/04/01/587/n/1922564/fe60d6be67ebe4b0bbd6f1.79749549_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/04/01/828/n/1922564/9432574867ec361a713285.06370027_.jpg)