Summary

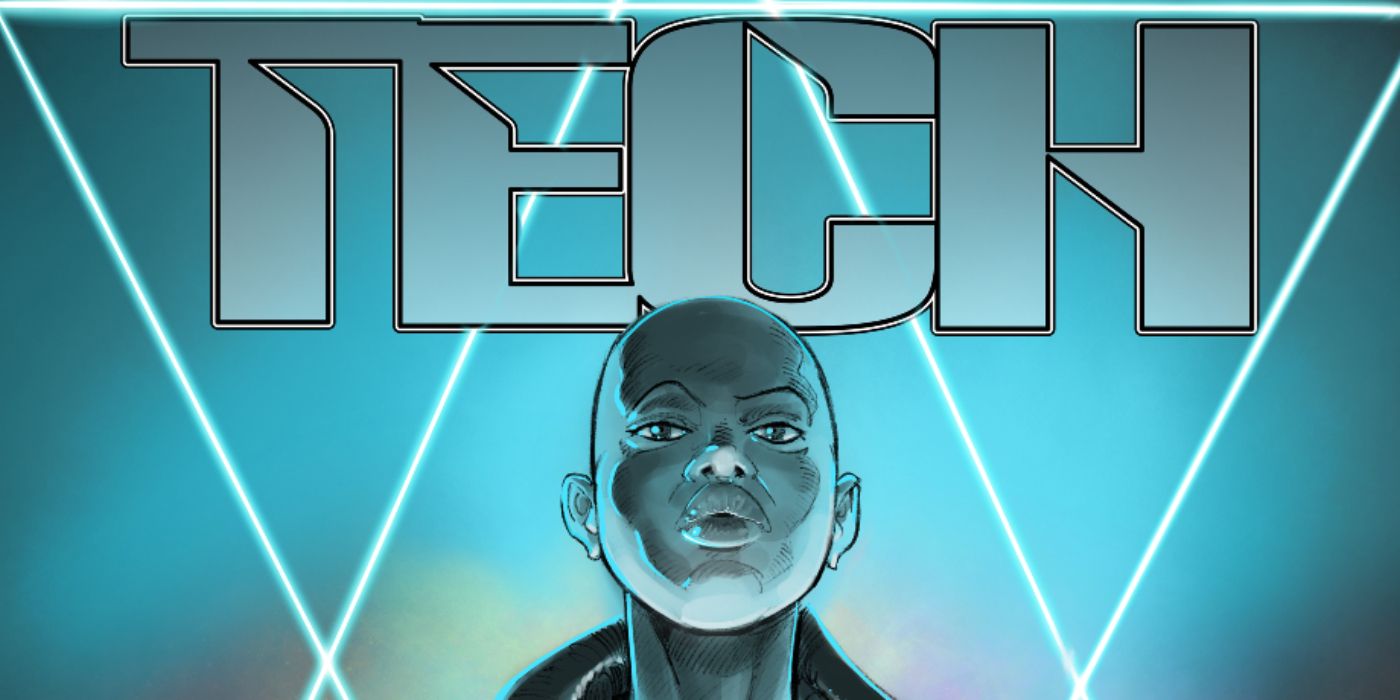

- TECH is a graphic novel by Vincenzo Natali (Cube, Westworld) that combines hard science fiction with narrative minimalism.

- The protagonist, Shel, has been exposed to advanced technology known as “modules” throughout her life, leading to genetic abnormalities in her and her daughter.

- While a bit short, the graphic novel features stunning visuals and excellently executed action sequences that showcase Natali’s background as a filmmaker and storyboard artist.

It’s easier to put people into boxes and define them like food labels than to understand their multitudes; we like to frame ‘the self,’ despite its illusory boundlessness. On an artistic level, it can be dissonant to see a filmmaker like Michael Mann make a literary sequel to Heat, or a surreal comedian like Tim Heidecker make genuine, catchy pop music. Director Vincenzo Natali is best known for directing great films like Cube, Nothing, Cypher, and Splice, but he began in the industry as a storyboard artist and has been a long-time lover of comic books. He’s now released his first graphic novel, TECH, a passion project seven years in the making.

Natali obviously pours himself into this graphic novel. As its illustrator and writer, he has total creative control, and it’s a clear reflection of his interests and fixations. TECH somehow balances hard science fiction with a kind of narrative minimalism, focusing on lengthy, explosive action sequences and the tortured personality of protagonist Shel, an estranged mother using her skills to try and save her ill daughter. Meanwhile, Natali explores transhumanist themes about technology and the nature of self and reality, which all seems appropriate for one of the most philosophically thoughtful sci-fi directors of our time.

Relentless TECHnology

Shel, an abbreviation of Michelle, has a startlingly unique design to her. Looking a bit like Grace Jones and Vin Diesel combined, she’s an androgynous, almost alien-like woman whose very cellular structure has been compromised by an advanced technology known as ‘modules.’ These mysterious modules originate from a kind of code that’s being transmitted from space to Earth, where scientists manufacture them based on the code. They can be used for a variety of things (energy, water purification, weapon development, drugs), but they cause specific kinds of damage through exposure.

Shel has been exposed to the modules throughout her life as a con artist and thief with her mentor, Bronsky. They stole and sold them for years, and it affected Shel’s DNA over time. So when she gave birth to a daughter, the child had lymphatic problems, six fingers, and telekinetic powers. She couldn’t afford the medical bills, and there are scientists who are very interested in the child. And so, Shel needs to steal more modules to try and save the girl. The modules are a kind of interpretive tool without hard logic applied to them; they’re essentially an allegorical stand-in for technology and its exponential progression.

Related: Nothing Matters and Vincenzo Natali’s Movie Proves It

TECH never gets too deep into its own lore, and there’s surely some interesting mythology to develop from this. But even with 200-plus pages, the graphic novel rushes along at such a pace that it has little time for exposition. It’s a similar aesthetic used in the mangas for Ghost in the Shell and Akira, where complicated sci-fi backgrounds and expositional foundations are often eschewed. With little explanation, you are thrust into a specific time and place and forced to adapt. It’s a similar tactic used by the legendary writer William Gibson, who provides a foreword here (after seeing Natali’s work directing an adaptation of his book, The Peripheral).

For those who prefer more methodical pacing, this may be frustrating, as TECH is almost minimalistic in the amount of information it leaves open for interpretation. It creates a world but does not define it. One could say, Natali doesn’t label TECH or put it in a box.

A Visually Stunning Noir World

Shel’s plans are continuously complicated by different figures and groups with separate agendas. There are cartels, gangs, criminals, scientists, cultist armies, and a vast police force, all competing over these modules, and Shel is often dragged into the middle of it all. She fights one group and is saved by another group, which recruits her to help them; the police try to then recruit her to help them against the new group. Backstabbing, betrayal, and false alliances (the hallmarks of capital) proliferate throughout TECH to the extent that you realize nobody’s connection is truly tethered as a sure thing — except Shel’s yearning for her daughter, and perhaps her earlier working relationship with Bronsky.

Related: Every Vincenzo Natali Film, Ranked

As such, Natali creates an alienating noir world reminiscent of Blade Runner or Dark City. There are countless gorgeous panels which illustrate this, and almost seem like gothic Star Wars noir, with a hooded Shel walking among module-distorted characters that look like robots or aliens due to their cellular corruption. Predominately using cold grays and blues in most panels, TECH sets an immediately consistent tone that deviates at just the right emotional moments, allowing for warmer yellows and oranges when needed.

Things get downright psychedelic as geometric lines and purple colors override the panels on occasion, highlighting the transcendent powers of the modules. There are hints that this quasi-alien technology can be used to completely obliterate the self, with TECH positing one of the oldest but nonetheless most interesting themes of sci-fi — is egoic identity a prison, and is escaping it utopic, or does it necessitate the destruction of individuality and freedom altogether? It’s a question posed by everything from Invasion of the Body Snatchers to the Borg in Star Trek, and while TECH only flirts with the notion, it’s interesting enough.

Perfectly Executed Action Sequences

While TECH invites speculation about its themes and emotions without going all-in, it unequivocally embraces action sequences as a kind of narrative storytelling. There’s no holding back here, no flirtation needed. The action is expertly arranged, laid out in very clear, well-edited, and sometimes wordless sequences that are highly gripping. Natali shows his hand here as a filmmaker and storyboard artist, constructing eloquent and brutal shootouts and heists that feel genuinely cinematic. It’s all extremely clean and capitalizes on what graphic novels can do best.

At least half of the panels in TECH seem devoted to the action, which is the graphic novel’s best quality (alongside its gorgeous illustration). It works, though one wonders if a longer version of the story, with greater exposition and less speculative assistance, would’ve strengthened TECH altogether. There are a lot of wonderful ideas and characters here that almost get sidelined by the action. Then again, the kinetic swing of its action is the novel’s greatest asset, so diluting it with more story may be a bad move. It’s hard to tell — either way, TECH leaves you wanting more. You want more Shel, more modules, more background and context, and yes, even more action (it’s just that good). Until we get some deluxe edition, though, we’ll have to accept our portion of this lean, hard, and cold sci-fi story, one that resists being placed in a clearly cut box.

From Encyclopocalypse Publications, TECH is now available for purchase through the link below:

You can view the original article HERE.