Ultimately, the narrative of Antoine Fuqua’s “The Guilty” operates largely from the motto of “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” And yet, to be fair, screenwriter Nic Pizzolato (“True Detective”) does add a few different notes of commentary on American policing and ignorant masculinity that slightly distinguish his take thematically, and Jake Gyllenhaal delivers as one would expect, proving again that he’s one of the most consistent actors alive.

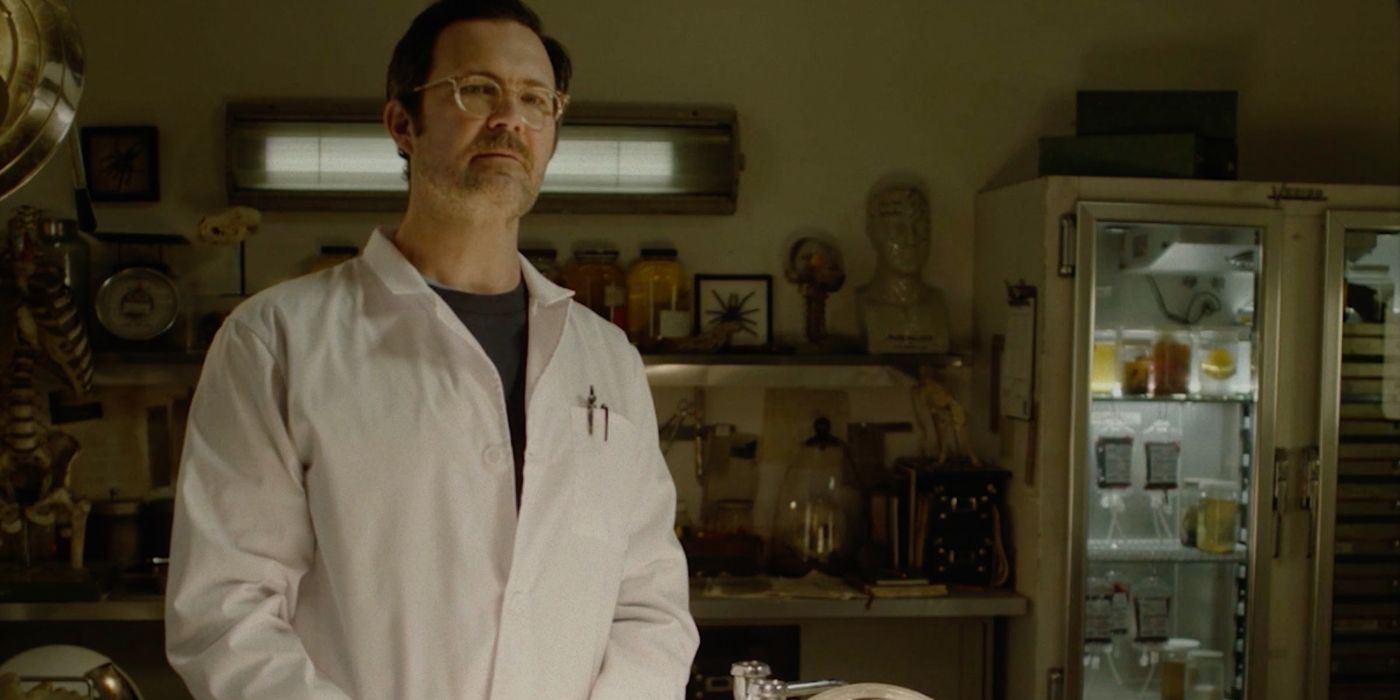

The skeleton of this thriller is pretty much identical, all the way down to the clever little prologue that sets up our protagonist as flawed while also adding a different backdrop that’s very California. We meet Joe Baylor (Gyllenhaal) on the night shift in a 911 dispatch center as his city of Los Angeles burns on massive screens in the background. He’s an asthmatic who has been forced to use his inhaler even more in this era of smoke and flame. He’s also wrestling with an undefined controversy that demoted this LAPD officer into a dispatcher and has led to calls from reporters. Finally, he’s dealing with a separation from his family, trying to call his daughter just to say goodnight. All of this oppressive tension leads him to quickly judge the people who call him, like when he scolds a caller for taking drugs or argues with another who has been robbed by a prostitute on Bunker Hill.

The breakneck pace of this thriller picks up when Joe gets a call from a terrified woman named Emily (Riley Keough, giving an absolutely phenomenal voice performance). She’s in trouble but can’t exactly say why, so Joe leads her through a series of yes and no questions. He figures out she’s in a very bad situation, and he soon gets incredibly invested in her nightmare, even more so after he speaks to Emily’s six-year-old daughter, who is home alone and terrified. He vows to save Emily and her daughter without really having any clear understanding of what’s going on. He acts on his interpretations and makes some drastic mistakes. Fuqua and Pizzolato carefully tie Joe’s behavior into errors in police work without ever making the film into a commentary on Defunding the Police. Still, the fact is that Joe is going to appear in court the next day for mistakes he made on the job, and there’s a throughline of what happens to him on this very long night that reflects how often cops act urgently and incorrectly, allowing emotion to overwhelm reason.

Of course, most of all, this is a taut genre exercise that Hitch would have loved—it has a similar forced perspective to “Rear Window” if you think about it. And Gyllenhaal completely commits, filling almost every frame of the 90-minute film. He conveys the tenor of a broken man from the very beginning, finding an emotional undercurrent of salvation in Joe that wasn’t fully explored in the original. There’s a sense that if he can save Emily that everything will finally be better. He will be a good cop, a good father, and a good man. Of course, anyone who places that much personal baggage on one case is going to make crucial mistakes. Gyllenhaal goes deep here—it will be too broad for some in the final scenes—but I was reminded how invested he is every single time. He never phones it in.

You can view the original article HERE.