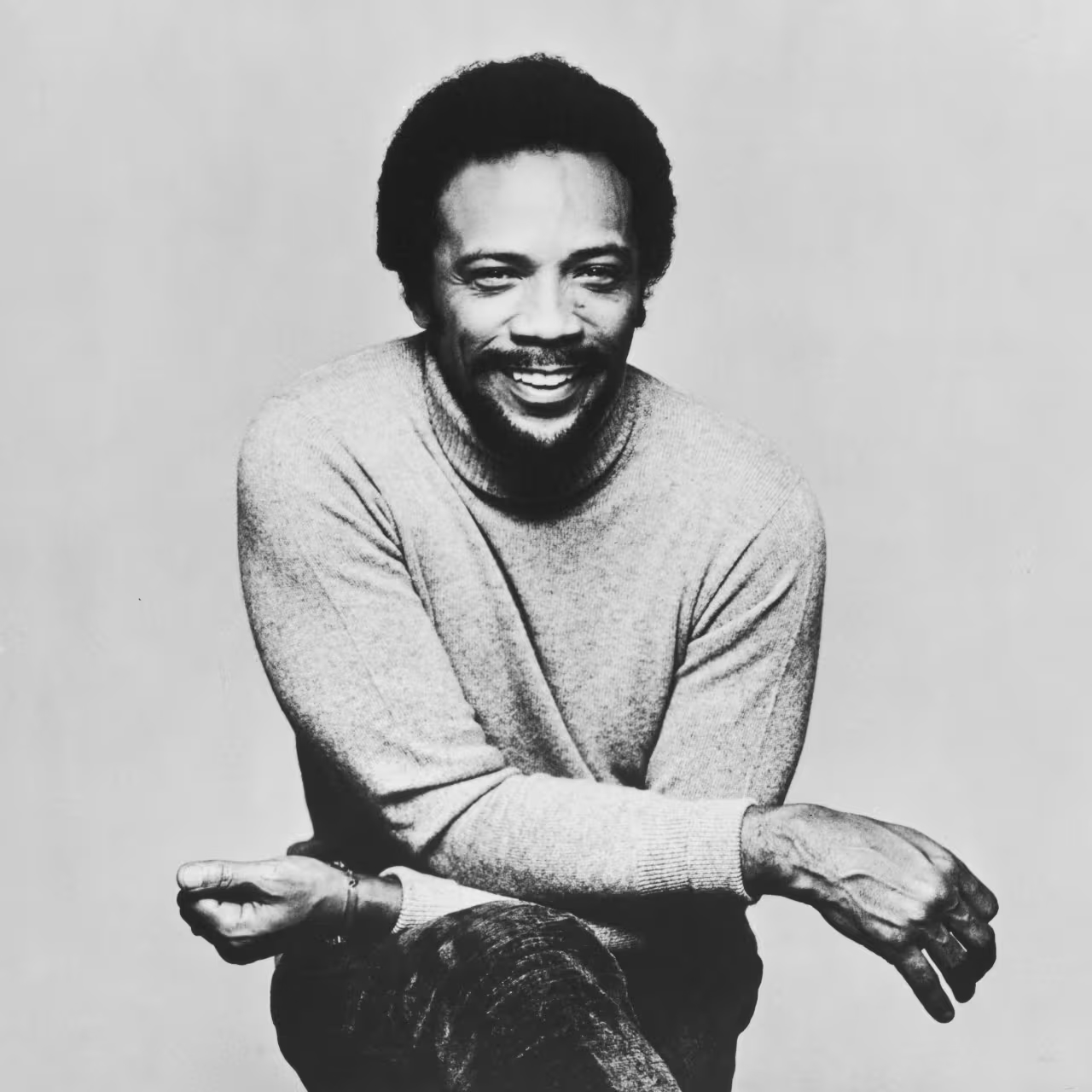

SCOUT TAFOYA

The modern film landscape has become so anemic and such an echo chamber that the idea of true revolutionary art seems almost unthinkable now. What would a movie look or feel like that stopped people in their tracks? That got everyone talking? That changed things? Melvin Van Peebles made them. “The Story of a Three Day Pass” uses the outsider gaze of the French New Wave to tell the story of his own alienation from a supposedly enlightened society. “Watermelon Man” took sitcom/Disney language and made one of the most shocking comedies of the century with it. And “Sweet Sweetback” was the only real Robin Hood story America ever needed, a chaotic, sexual, violent, unreasonable and Cool story of killing cops and getting away with it because the people want your freedom more than the authorities want you dead. He wrote novels, he staged plays, he was a mentor and a friend to young filmmakers who needed his hand on their shoulder (I was once told he and Spike Lee were both initially refused admission to “Do the Right Thing”’s Cannes premiere because they didn’t show up in tails, and I can perfectly picture them taking the news), but even if he had just made any of those three films his place in history would be assured. We needed him badly. Now more than ever we need artists who don’t see risk—they just see the truth and tell it.

PETER SOBCZYNSKI

My first, albeit glancing, encounter with the work of the legendary—and in this case, that word is not so much hyperbole as a simple statement of fact—Melvin Van Peebles came when I was about eight years old, and, like so many things related to my still-developing interest in all things cinema, was due to the efforts of Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel. By this time, around 1979, I was already an avid viewer of “Sneak Previews” and at one point, they did a special episode entitled “Movies that Changed the Movies” in which they took a look at films that had gone on to have enormous, trend-shifting influence on the industry in recent years. Some of the titles under discussion were ones that would have already heard of by that point—things like “Jaws,” “Airport” and “Easy Rider” while others were unknown to me. Falling into the latter category was “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” his groundbreaking 1971 film that he wrote, directed, co-produced, edited, scored and starred in about a Black man on the run from police after being arrested for a crime he didn’t commit. Produced outside a Hollywood system that would never have even dreamed of putting a penny into it—even though Van Peebles had already worked for a major studio with his previous film, the wild 1970 comedy “Watermelon Man”—it went on to become a huge hit with chronically underserved Black audiences who were at long last able to see a movie that represented their struggles and has often been cited as a precursor to the popular blaxploitation genre. In truth, the film was not exactly a true blaxploitation movie—while it contained plenty of action, sex, violence and other easily exploitable elements, it was far more inventive and radical than most of those films both from a formal perspective, utilizing cinematic techniques that were more common found at the time in European cinema, as well as a political one—this may have been a tense action-thriller but it was ultimately one that was genuinely about something more than cheap thrills. If anything, it was more of a precursor of what would eventually become known as the American film movement.

Of course, I didn’t know any of that at the time of this “Sneak Previews” episode. All I knew is that a.) the brief clips featured on the show were utterly unlike anything I had seen up to that point, b.) it had one of the most memorable titles that I had ever heard and c.) there was no way that I was going to be seeing it anytime soon—even in the highly unlikely event that the film appeared in the profoundly white-bread midwestern suburbs where I grew up, I was still young enough that merely saying the full title would have earned myself at least a mild reprimand from my parents. However, I never forgot it and when I finally got a chance to see it on home video a decade or so later, I leapt at it, albeit with a certain amount of apprehension that it would prove to be one of those movies that may have captured the moment when it was made but which did not exactly age very well. That was not the case. The film was still a potent and oftentimes radical piece of cinema that remained as vibrant, alive and relevant as it was when it first came out.

You can view the original article HERE.