Manic Street Preachers have spoken to NME about their song ‘Dear Stephen’, inspired by Morrissey, the road to their new album ‘Critical Thinking’, and how they’re already thinking about their next move.

Released today (February 14), the Welsh rock veterans’ acclaimed 15th album was said to be born of “eternal uncertainty, doubt and desire”. Bassist and lyricist Nicky Wire told NME how that allowed for “a different kind of record” to what you may have heard from the Manics before.

“Albums are a reflection of where your mind is at – certainly in the Manics’ world,” said Wire. “Sometimes you have to let that honesty out. I just went off myself a bit, but I always find myself to be my most dependable source of inspiration. I’m starting to lose that – but that’s different to the lyrics from James [Dean Bradfield, frontman] on the album; his three songs have more of a sense of optimism to them.”

Around the release of the 2022’s ‘The Ultra Vivid Lament’, Wire described the predecessor album as an “exploration of internal galaxies” that saw him “digging deeper into himself” and “on the retreat”. The Wire-sung opening title track ‘Critical Thinking’ – described by NME as “a snarky diatribe spitting back at the false empathy in social media’s conveyor belt of empty platitudes” – appears to see him on the attack once more.

“The only thing I attack on this record is myself,” he told NME about ‘Critical Thinking’. “The moral judgement on this album is very much the mirror, maybe with the exception of ‘People Ruin Paintings’ which is a bit broader. ‘Critical Thinking’ the title track conveys a different kind of lyrical nastiness and is very much a warning to the self: the idea that the train is as important a muscle as any other. You have to go to the gym for the brain, which for me was just writing it all down and trying to come to some different perspectives.

“I know it sounds really fucking nihilistic and narcissistic; it’s just the way it was. We don’t have time to really interrogate what kind of album we want to make or how we do it.”

Bradfield, meanwhile, told NME how having “no real mission statement” or concept for ‘Critical Thinking’ allowed the band “a sense of freedom”.

“As you get older and as all the concepts, ideologies and understandings that you’ve grown up with start to dissemble and crumble around you – whether it be left, right or left of centre – once you realise that they become a separate tense and economies work in different ways – the game is up,” said the frontman.

“You can’t think the way you used to think. You’ve got to have a looser way of thinking and see what comes out of it. That’s what we did with this record.”

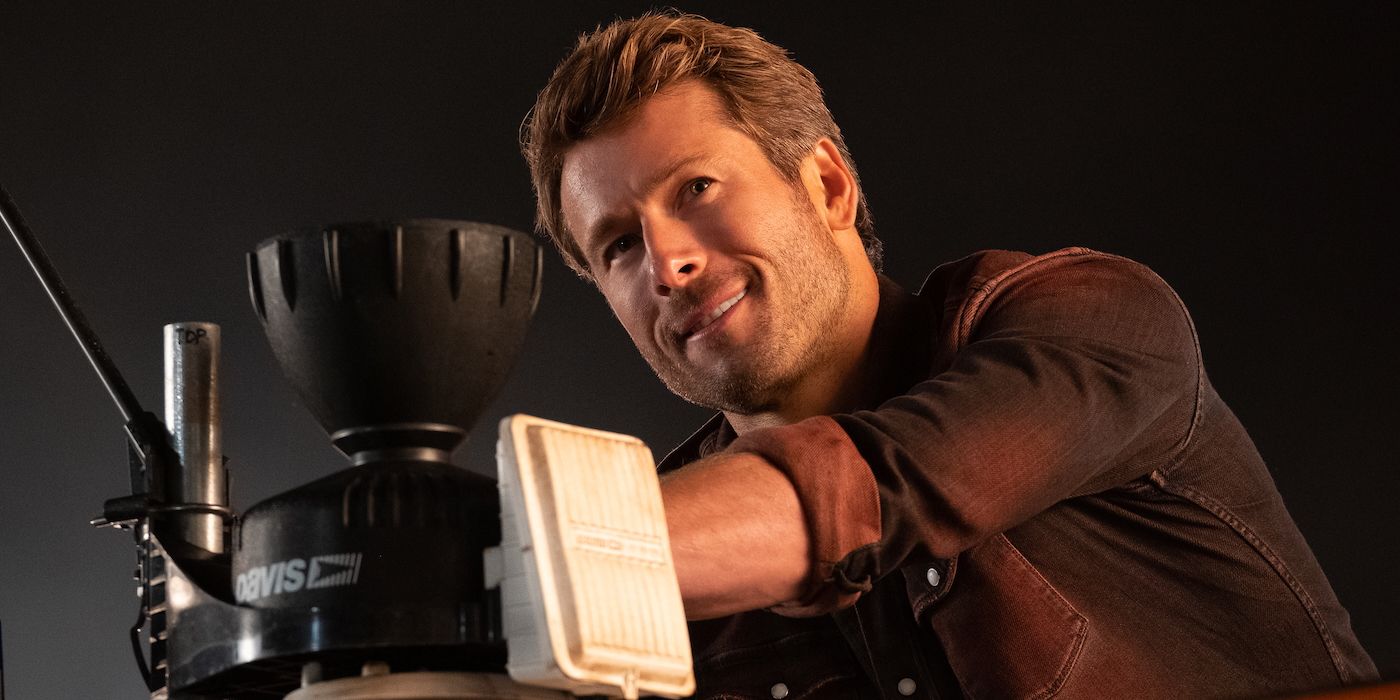

Manic Street Preachers, 2025. CREDIT: Alex Lake

Bradfield pointed to the opening title track along with the furious closer ‘OneManMilitia’ (also sung by Wire) as the extremes of the album.

“They’re two songs that rage in a very Nicky Wire-esque way, they’re lyrics that live on their own,” he said. “They don’t ask for any empathy, they don’t ask for support, they don’t ask you to agree; they are what they are. He’s done that many times before but even better this time.

“Those songs stuck together, but then you’ve got ‘Hiding In Plain Sight’ which is the polar opposite and very empathetic towards himself; it’s asking to be listened to in the right way. ‘Decline & Fall’ really talks to us and the world we live in. It really describes where we are and how we feel. It doesn’t really wallow in any self pity, it just tells it how it is.”

At the centre of the album is ‘Dear Stephen’ – inspired by a postcard sent to Wire as a teen from Morrissey at the request of his mother after he was too ill to attend a Smiths gig.

Many reviews of the album and fan commentary around the record have assumed that the line “Dear Stephen, please come back to us” is pleading for a return of Morrissey in his ‘80s prime before the many controversies that have surrounded him in decades since. However, Wire said that this is not the case.

“The only moral judgement on this album tends to be about me,” he admitted. “The song is about many things and it’s multi-layered. It’s about me critically looking at my own reliance on the past – about why those years were so scorched onto me. It goes for a lot of people, to be honest, but being between 12 and 18, I don’t think I’ve ever shaken them off for the imprint they’ve had on my aesthetic appreciation of music, literature and film. It’s an investigation of that.

“The idea that I had this postcard off Morrissey as well that said, ‘Get well soon’ and I kept it, it was quite a worthless thing that I imbue with so much meaning. It’s about so many different things but mainly about not being able to get out of that, and the amazing comfort and joy it brings. It’s a love letter to my former self as much as it is everything else.”

Bradfield explained how Wire discovering the postcard in the aftermath of his mother’s death made it “all the more prescient”.

“She used to send off letters and postcards to venues when she knew his favourite band would be playing there,” the frontman recalled. “Whether Whitesnake, Rush or Echo & The Bunnymen, she would send a postcard to the venue saying, ‘Dear Mr McCulloch’ or ‘Dear Mr Morrissey, my son is a big fan of yours, can you please send him a postcard…’

“When he gave me the lyric, he told me that it was about the power of the object over him. So many of Morrissey’s lyrics were about being ill or had references to him not feeling physically well for the task of life itself. It was ironic that he had this postcard back saying, ‘Get well soon Nicholas’. The song was purely about the power of this inanimate object over Nick and his emotions, and Nick’s inability to escape the influence of those times that are still in possession of him. Those times still inform him and take him by surprise.”

Bradfield said that it felt “beautiful” to paraphrase The Smiths’ ‘I Know It’s Over’ for the lyric “it’s so easy to hate, it takes guts to kind” – and how it was “reminiscent of how we felt in those times in the Valleys”.

“When you’re 16, 17 or 18, music is literally a portal into another world, a lifeline or a spark that helps you become another person,” he added.

The singer and guitarist described the idea that the bassist was commenting on Morrissey’s present day character as “over-analysis”, with Wire agreeing that there’s always an element surrounding Manics’ songs.

Each Manics album famously comes adorned with a quote that speaks to its character. This time it’s ‘I am a collection of dismantled almosts’, by Anne Sexton.

“The ‘almosts’ come after that period [of the ‘80s],” said Wire. “Everything seemed so certain back then. I still like everything I did back then. It’s all about critical thinking – trying to re-evaluate who you are and why you like those things.

“If everyone had the same amazing fucking benefits I had when I was growing up – the music that was around, the parents that I wish everyone could have – it wasn’t anything other than working class but it was just so culturally-enriched.”

The Bradfield-penned ‘Brush Strokes Of Reunion’ follows in a similar vein, inspired by “an object with power over my emotions”. “It’s about how there’s a part of my house with an oil painting by my mum,” he revealed. “I go there to write now and again or to read, and since my mother died in 1999, that picture has held a significant power over me.”

Manic Street Preachers, 2025. CREDIT: Alex Lake

The two other tracks with lyrics by Bradfield are ‘Being Baptised’ (written about a day spent with Allen Toussaint while filming an episode of the BBC’s Songwriter’s Circle in 2011) and ‘Out Of Time Revival (“about the malaise of post-lockdown when I was trying to turn every opportunity into a really bad black and white B-movie”).

“I thought, ‘Stop trying to find meaning in life and answers in all these things’,” he said of the latter. “It’s a hopeless cause: writing a song about overanalysing life and being too pretentious. As Neil Young said, ‘Just find a chord and dig in’. Keep a steady beat and you’ll get there.”

Ultimately, that compulsion to carry on is what lay at the heart of ‘Critical Thinking’ in reminding the band of the purpose of a record. “It makes you realise that perhaps you are talking to yourself a little bit more than you realise,” said Bradfield. “It doesn’t always have to lead you to something that feels like therapy. Writing songs is just a place where you can be yourself. I’ve spent most of my life writing music for Nicky and Richey’s lyrics and that’s something that I just love. There’s a real thin line between trying to say you’ve found the key to life and just dig in.”

Earlier this month, the band played two album launch gigs at Pryzm in Kingston on February 1 – marking 30 years since guitarist, lyricist and propagandist Richey Edwards disappeared back in 1995 ahead of the US promotional tour for seminal third album ‘The Holy Bible’. He was officially declared dead in 2008 in order to settle his affairs with his family.

“It never fails to flaw me, to feel that he was only 27 when he disappeared,” Wire told NME. “He’s been gone for 30 years and time is incredibly cruel sometimes.”

Admitting that such milestones hit the band hard, he continued: “And I know that they do with his sister, family and friends. It’s not just about Richey the band member. There’s the brother as well and everything that goes with that. It almost feels unreal to think that 30 years have gone by. It’s pretty hard to structure your mind to take that in.”

Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers, backstage in Bristol, 1994 CREDIT: Tristan Quinn/Gems/Redferns

Still, Edwards’ influence and ideas echo into their current work. Wire pointed again to the new album’s title track. “Sometimes you reign yourself in, and I always thought that critical thinking was the power to reject,” he told NME. “Whether that’s reading James Baldwin, J.G. Ballard, Susan Sontag, whatever – that power to say, ‘Do you know what? I’m not sure about this’.

“It’s that ultimate question mark. With Richey as well, I always feel that he’s doing that with his lyrics to ‘Archives Of Pain’ or ‘P.C.P.’ [from 1994’s ‘The Holy Bible’] It’s about that idea of your mental training to sit back and reign those fridge magnet philosophies in.”

Bradfield mused: “That’s a very strong motivation for someone like Wire or Richey to write lyrics – to ask, ‘How did we get here?’ Writing that song is a much more complicated process than it used to be because it’s just as easy to disagree with your own side’s operations as it is your natural opposition.”

Finding their own purpose through so much unlocked a “freedom” for the Manics, as both Bradfield and Wire describe it. “You can get totally entrapped and obsessed, whether that’s over critical opinion or just getting on the radio, streaming or your own internal critique,” said Wire. “Time is really precious. The one thing I wish other people could have is all the luck that we do. When we’ve got inspiration we just go in the studio. We’re good enough now whether we’re on our own or together to get something good.

“It’s really important that we still feel that we have that energy.”

The years since ‘The Ultra Vivid Lament’ saw the band revisit two of their more divisive albums – reissuing the scuzzy and political ‘Know Your Enemy’ and the personal synth-pop of ‘Lifeblood’ to mark their 20th anniversaries. Somewhere between the fury and introspection of those records, Wire admitted they found inspiration for ‘Critical Thinking’ (“It’s like a hybrid of both of those – perhaps it had more of an influence than I realised”) with the sonic departure of ‘Lifeblood’ and 2014’s Berlin and kraut-rock-inspired ‘Futurology’ sparking ambitions for their next LP.

“It was interesting going back to ‘Lifeblood’ – an album that I wasn’t sure about for a long time, apart from one or two songs,” said Bradfield. “Now, I feel like it was a really successful experiment. For me to have to have this amount of time to realise that is quite disconcerting. It makes me realise that in terms of processing information on a sub-intellectual level, I’m still the runt of the pack. It took me years to realise that ‘Lifeblood’ was a good record. I’m not saying I want to do a record like ‘Lifeblood’, but dissociating yourself from emotion can be a help sometimes.

“We were talking the other day and the only thing we’ve got on our heads is that we’d like to go abroad and record. We’d love to keep it cold and European. I’m not saying that’s going to make it ‘Futurology’ part two, but that’s what’s in our head. We haven’t even released this record yet, so the mere fact that we’re talking about what we could do next is quite a nice sign.”

Wire pondered some of his bandmate’s suggestions of new producers recording their next album in Hamburg, adding: “James has this random nature of explosions of ideas which need to be harnessed really quickly or they’ll just go.

“‘Futurology’ is one of the best Manics albums and it has stood the best of time. For me, ‘Lifeblood’ and ‘Futurology’ fit together in terms of the sheen. I could definitely see us following the muse on that level.

“I haven’t written many words for a while because it’s good to take a break from the album you’ve just done and not repeat yourself. This one is meant for the dark night of the soul and I’m sure the next one will be different from that. Whether it’s broader, whether it’s more macro in outlook. We’ll see.”

Wire added: “There’s always a song to be written. A lot of it is just down to willpower now and seizing that moment of inspiration. When you get that moment, you have to work quick or it disappears.”

Noting how they’ve travelled beyond the midlife of their career, Bradfield said that the band had grown “hard-nosed” about what to do – but still had reason to go on.

“Once you realise that you’re closer to the end than the beginning, that really focuses you,” he said. “It’s just maths: this is our 15th album and there’s no way we can do another 15 records. You just want to do that until you can’t.

“If we don’t want to do something then we won’t, but if you still enjoy each other’s company enough after so many years and not want to kill each other then it’s definitely something worth persisting with.”

Check back at NME soon for more of our interview with Manic Street Preachers.

‘Critical Thinking’ is out now, with the Manics kicking off a UK headline tour in May. Visit here for tickets and more information.

You can view the original article HERE.