For decades, the games industry has failed to protect the creatives that have allowed it to flourish. The latest UK Games Industry Census, provided by trade body UKIE, points out that 38 per cent of workers within the games industry live with anxiety, depression, or both.

Speaking to NME, Safe In Our World charity director Sarah Sorrell points out that the figure is made worse if you look beyond the games industry, where the figure hovers between 17 and 18 per cent.

There’s no shortage of things to blame. A long-standing culture of crunch — working brutally long hours to hit tight deadlines — means developers are frequently overworked. This often leads to burnout, where the effects of long-term stress manifest in a range of physical and emotional symptoms. These experiences can be devastating to workers’ mental health, and the process often chews up the very passion that drives creatives to the industry.

In the past, these issues have been (wrongly) considered to be the cost of doing a job you love, and it’s been somewhat normalised by their prevalence at the industry’s biggest studios. While investigative reports and social media whistleblowers have led to much more accountability for leadership pushing crunch, its effects — and the games industry’s wider issues with mental health — are still fighting to be addressed.

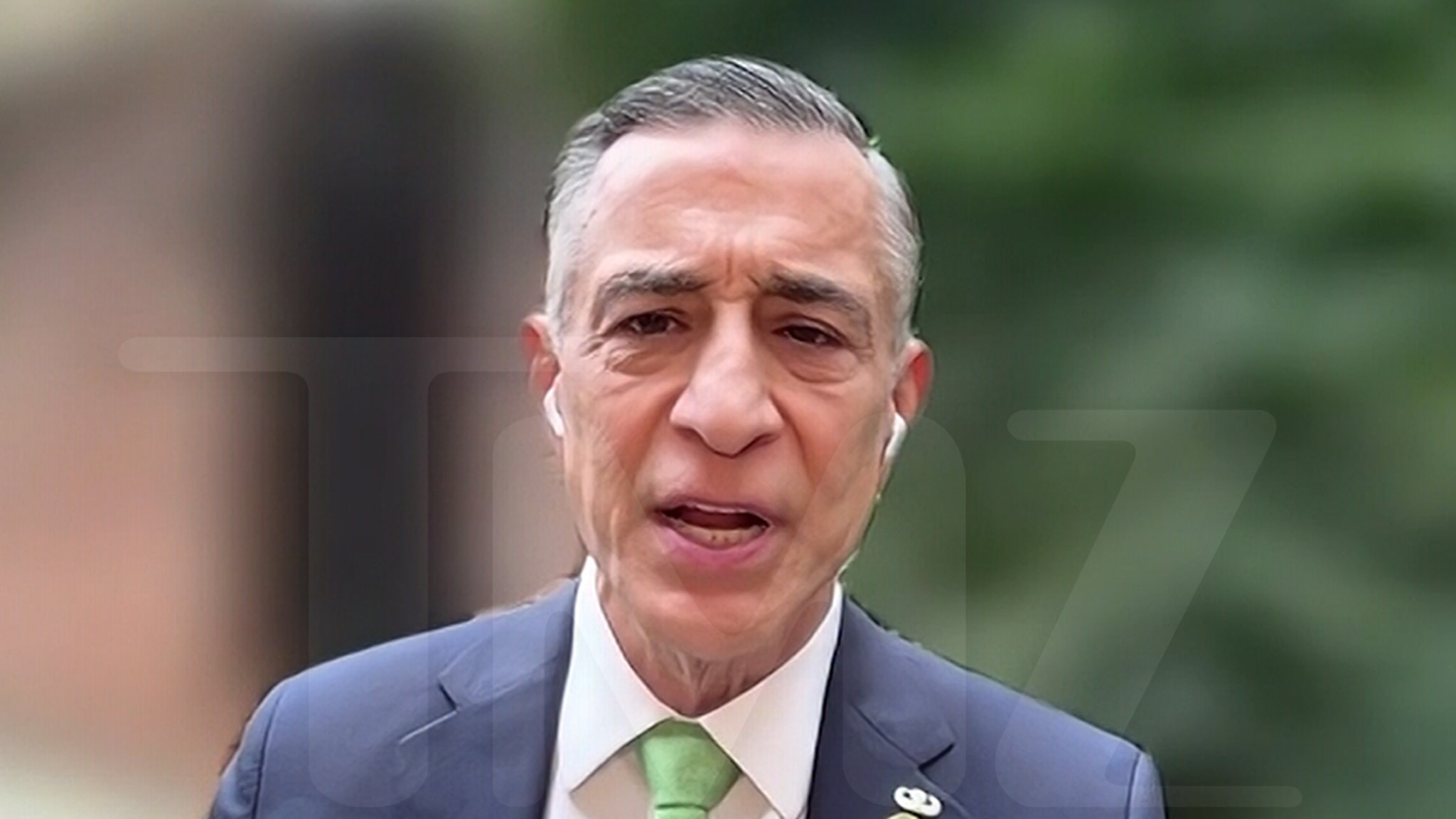

Games Mental Health Summit. Credit: BAFTA/Alecsandra Dragoi.

Founded in 2019, Safe In Our World aims to raise awareness of mental health in the games industry and destigmatise discussions surrounding the topic. In May, the charity teamed up with arts charity BAFTA to hold the inaugural Games Mental Health Summit, which was hosted at BAFTA’s London headquarters.

The summit invited a mix of motivational speakers, industry veterans, and healthcare specialists to lead talks on their own experiences and offer practical advice on taking care of mental health. Topics ranged from advice on setting boundaries and avoiding burnout, to improving the industry’s inclusivity and mental health representation in games. Though the subject matter varied, they all offered tangible advice on how listeners can take care of themselves — driving practical change that Sorrell says the industry is “desperate” for.

“People will tell you that they twisted their ankle when they were gardening on Saturday,” says Sorrell. “They won’t tell you they were awake on Saturday night with crippling anxiety. That’s the bit we need to change and make a natural topic of conversation — practical change is something we are desperate to do within our industry.”

Games Mental Health Summit. Credit: BAFTA/Alecsandra Dragoi.

Luke Hebblethwaite, head of games at BAFTA, agrees. “The destigmatisation of the discussion of mental health is a journey, and we are still on that,” he explains. During the summit, Hebblethwaite participated in a fireside chat where he spoke of his own mental health experiences, which he says was “rewarding” yet “slightly terrifying” due to it being a subject he’s rarely discussed publicly. Hebblethwaite’s own chat fed into the summit’s wider goal: to raise awareness and destigmatise mental health discussions, while driving practical change.

“We wanted to put on an event that was useful,” says Sorrell. “The biggest outcome for me is that people went away with outcomes, with learnings. There were so many people there with notebooks, furiously scribbling away, and from the people I’ve spoken to, people have come away with real practical skills to actually solve some issues they’ve been thinking about for a while.”

Hebblethwaite and Sorrell suggest the attendance for a talk on avoiding burnout — which was filled to capacity — is telling of the industry’s problems. While studio heads like DoubleFine’s Tim Schafer have been vocal about pushing back on the normalisation of crunch, the practice is far from eradicated and remains a major cause for burnout.

“Working an employee those kinds of long hours is never going to work out in the long term — they’re going to hit burnout, and they’re going to leave,” says Sorrell. “That’s a massive mistake that has been happening in our industry, which we really need to address.”

Luke Hebblethwaite (right) at the Games Mental Health Summit. Credit: BAFTA/Alecsandra Dragoi.

To do so, Sorrell says that the industry needs to change its perception of working long hours, and raise awareness of mental health issues like burnout so that people can better recognise — and act on — their warning signs.

“A lot of people who come into our industry feel like they’ve got their dream job in video games and may even be working on a game they’ve always loved,” she explains. “They’ll give it their all, they’ll give it 20 hours a day. A lot has to be done from a leadership perspective to say no — it’s not good for you — and lead by example. We need to remind people that’s not a good idea.”

“Once you hit burnout […] If you’re at crisis point, it’s too late,” she adds. “You’re going to need medical intervention quite often, and you’re going to need time off. If you are aware of burnout and its signs, you can start to put [solutions] in place beforehand.”

Safe In Our World hopes that with continued education and discussion, more people within the games industry will have the tools to avoid burnout and support themselves. To that end, both Sorrell and Hebblethwaite agree not only that industry perceptions are shifting, but employers in the UK are eager to do better. As an example, Sorrell points out that she was recently approached by a summit attendee whose agency has since changed the way it conducts interviews to improve support for neurodiverse candidates; while Hebblethwaite feels encouraged by the industry’s willingness to act.

FuturLab CEO Kirsty Rigden at the Games Mental Health Summit. Credit: BAFTA/Alecsandra Dragoi.

“If you look at how the games industry — or any industry — discussed this topic five or 10 years ago, you can see a massive amount of change,” says Hebblethwaite. “I think that change will continue, but it’s not something that will continue passively. We have to be active within that space. We need serious organisations — like BAFTA, Safe In Our World, and trade associations — tackling it, but also, games businesses themselves have to take ownership of this. We can’t do it for them.”

Likewise, Sorrell is thrilled with the results of BAFTA and Safe In Our World’s work, but acknowledges their job is far from done. The pair are hopeful that more summits can be held in the future, and Sorrell is keen to drive this momentum into tangible change.

“We’ve started that movement within the industry to come together and look after our teams and talent,” says Sorrell. “I am seeing a lot of improvements, but we’ve got a long way to go. We want to make sure that we’re here not just to get people started, but to keep them on their journey. Wellbeing in the past has been seem as a bit of a fluffy and vogue — ‘Yeah, let’s tick that box’ — then six months down the line, work’s really busy and that gets completely forgotten.”

“What we’re here to do is keep that momentum going, keep that conversation going, and keep reducing the stigma that does still exist in our industry around mental health,” Sorrell urges. “It’s an invisible illness, isn’t it? So we’ve got to keep talking about it — because people can’t see what you feel.”

Recordings of the Games Mental Health Summit will be uploaded to BAFTA’s YouTube Channel.

For help and advice on mental health:

You can view the original article HERE.