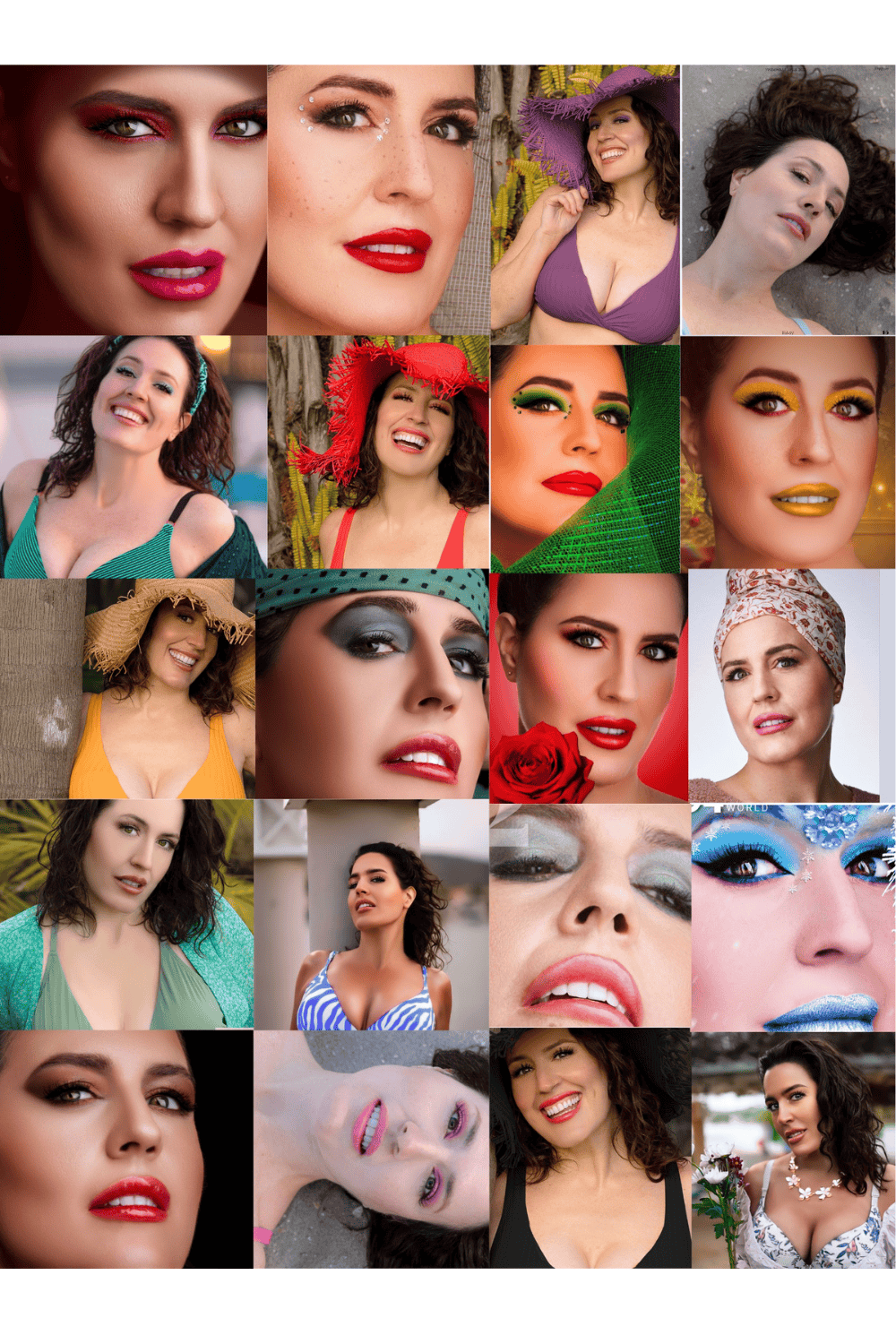

“The Worst Person in the World” emulates Julie’s sense of self-discovery through this sensual, unfixed sense of style. Hallucination sequences, voice-overs, the outside world freezing still. What shifts did you each want to convey in Julie, and how did you select the formal innovations that would reflect that inconsistency?

JT: In a way, that’s a question for both of us, because it’s two-part, I sense. I can talk about my intentions, and then Renate can talk about the transformation process. To be quite honest, my job is to tell the story and come up with these formal things, to set the scene. What I find really admirable is how Renate is able to transform, subtly, as we come to the end. I told her early, “I would love people to feel at the end of the film like we’ve been through a big space of several years and someone’s development of life.” And how Renate does that is still a mystery to me, but it seems to be working for everyone that sees the film, which is incredible. There’s a great hair and makeup department and clothes, but there’s something intuitively smart about how she deals with the physical appearance, the movements, and the emotional awakening of a character over so many years, when it’s not shot chronologically.

Form, though, is something that Eskil Vogt, myself, and the editor Olivier Bugge Coutté are very concerned with. We come from being fans of “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” the French New Wave, Nicolas Roeg’s “Don’t Look Now,” all these films that are trying to talk about how time and memory can be dealt with, in cinema, in a way unique from all other art forms. We can cut around and time-layer. You also see it in Bergman in a different way, how he makes dream sequences and the fantastical suddenly appear in the middle of films that are sometimes quite rough and real and human and raw. To create films where there’s both that sense of naturalism and appearance of identification from the audience, then tweaking that into a mushroom trip or an almost-musical sequence of running around Oslo when Julie freezes time, it liberates the audience to have a bigger thematic scope to feel the film in—rather than just a kitchen-sink drama with two people talking all the time. Certainly, there are long dialogue scenes in this film, and I’m very proud of them. But the dynamic between intimacy and the bigger scope of playful movie-making is what I’m curious about.

RR: When I read the script, I felt like every scene contained so much. It was so rich, so full of complexity. With the mushroom trip and going back and forth in time, you got a sense that you’d been everywhere: in time and space, and also emotionally, with all the characters. I was really scared of not getting all those nuances, and not having in the performance all the details that I felt were in the script.

We talked about that very early, how her body language should reflect her state of mind. Julie goes through a journey of being very restless, not being able to decide on anything, not knowing what to do in life or who to be with, and not being able to accept herself. And then she is forced to look at herself, and she goes through the loss of someone, and the loss of the image she had of herself. In the end, you see her actually finding peace and acceptance in being herself.

You can view the original article HERE.