Documentary filmmaking is a sometimes impossible task by definition. Just like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, the very act of filming a subject changes their nature (i.e. people are aware of the camera, and editing choices show subjectivity). Much has been said about this, and filmmakers have experimented with all sorts of ways to escape the paradox (or embrace it). Chinese director Wang Bing has a tried and true tactic that changes the nature of his documentary work — he has a radical approach to time that allows audiences to immerse themselves in the worlds he films. With his cinematic behemoth Youth, a trilogy of films about textile workers, he committed five years of his life to filming, and four years on and off to editing.

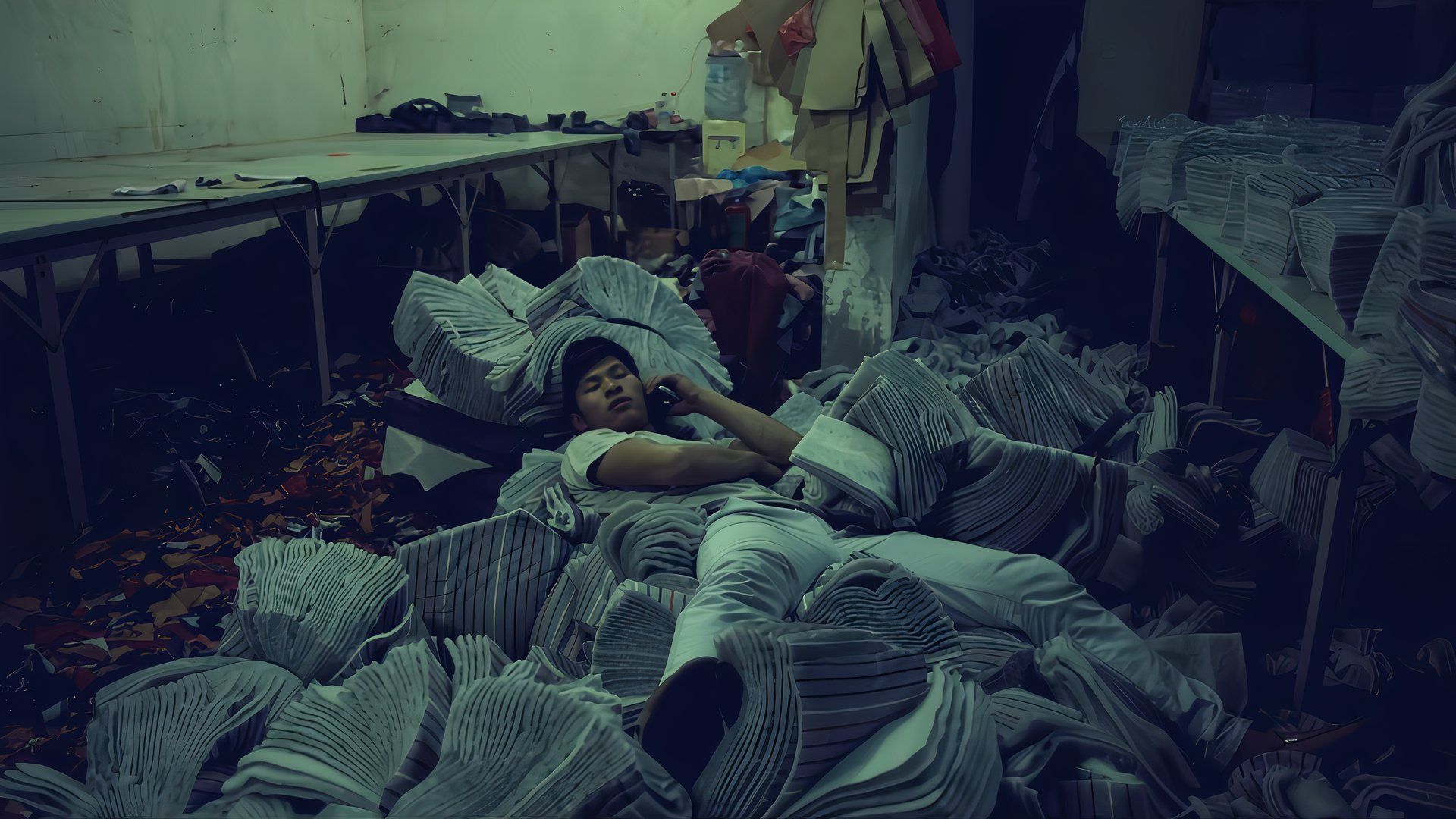

Bing embedded himself in Zhili, an industrial town 150km outside of Shanghai, from 2014 to 2019 in order to document the lives of migrant workers who come to the town seasonally and live in dorms while they work 12 or more hours a day. This began as the film Bitter Money, which Bing has referred to as a kind of test run for this much larger project. He also experimented with the art installation 15 Hours, which is a 15-hour long static shot of one room of workers toiling away.

It was all preparation, though, for his Youth trilogy, three similar but also different films that embed viewers into this world just as Bing was. Running nearly 10 hours between the three films (Spring, Hard Times, and Homecoming), Youth obviously requires deep patience and commitment, but it’s a transformative experience.

How Wang Bing Captured the Work of Youth

The film focuses on a group of young textile workers in Zhili, a town in the Wuxing District of Huzhou, located 150 kilometres outside of Shanghai. Every year, young people leave their rural villages and migrate to the manufacturing town. The workers are in their twenties, some in their thirties. They sleep upstairs, in dormitories, because they come from far away, sometimes over 2,000 kilometres. Their dialects come from different regions. They work tirelessly with the hope of one day having children, buying a house or starting their own business. Friendships and romances fold and unfold as the seasons pass. Geographical dispersion, financial instability, and economic and family pressures ravish their innocence and youth. Wang Bing will spend a year with them in Zhili: at work, at home, on the Internet, every day of their professional, romantic relationships and friendships.

Director Wang Bing

Runtime 9h 51m

Awards Nominations

Producer

In theaters

Pros

- A brilliant experiment in filmmaking that warps time and creates compassion and empathy.

- A fascinating study of labor, bargaining, late capitalism, and Chinese industrialism.

- A wide variety of interesting people and situations present themselves over three films.

Cons

- These films require commitment and are not for easily restless or bored audiences.

300,000 people work in Zhili, and there are more than 18,000 individual businesses. Bing studies dozens of workers and multiple businesses and their managers; individuals stand out, of course, but it all blends together in an eerie, sad way that presents a massive analysis of labor. The initial budget was set to cover six months of production, but Bing stretched it to six years. There were six cinematographers, filming in shifts three at a time.

Related The 23 Best Documentary Films of 2023, Ranked

Documentaries were the only genre and medium that flourished fully in 2023. These are the best documentary movies of the year.

Bing summarized the project and intent to Projektor, saying, “The narrative is simple. I wanted to capture the reality of China since it implemented major economic reforms in the 1980s. More specifically, within the Yangtze River Delta. A lot of people came to urban centers from rural areas upstream of the Yangtze River to look for work. Most of them were farmers who eventually became migrant workers.” He added:

I didn’t just want to empathize with them; I wanted to place myself in the same position. I wanted to be on equal footing with them so I could accurately capture their reality. Instead of trying to look down or up to them, I just wanted to see them as my peers.

As such, Wang Bing took the phrase “fly on a wall” as literally as possible, becoming a natural, expected presence in the workers’ community over the years. He described it this way to Metrograph: “We [the crew] live in a small town nearby; we come in the morning, film all day, and leave at night. It takes a lot of time to understand your subjects, to understand all the different characters and personalities in a particular location, and to build rapport so that you can have their trust and capture something authentic. That’s how we accomplish this, using time as a way to somehow acculturate into their environment.”

Marrying Form & Content with a Decentralized Structure

Wang Bing presents a world and not a narrative. Youth has different ‘parts,’ most of which have some story (a romance, a conflict, a negotiation, etc.), but they aren’t connected in any linear way that progresses like a movie. We’re introduced to dozens of people with their names, age, and hometowns; they’re mostly between 16 and 25, though some are older. We might spend 15 minutes with someone and then never see them again. We have no understanding of time, what day it is, or month, or year. We just know which factory we’re at.

This scattered approach mirrors the subjects of the films. The workers become anonymous to management and blend together, some returning for the next season, some not. They come and go, and while they’re in Zhili, they do the same repetitive work day in and day out. They sleep in unhealthy, claustrophobic dormitories, the days bleeding together. Every single group gets together and tries to negotiate for higher pay; every single manager shoots them down, sometimes offering just a few yuan more. Time is money, they say, and we watch that transference take place practically in real time. That’s the brilliance of the scattered style of Youth — it’s a structure that mirrors these people’s lives and the decentralization of China’s economic system. As Wing Bang told Film Comment:

“In production facilities in China, it used to be that everything was centrally governed. The system governed everything. If you didn’t do the job the way they wanted, you would be punished, disciplined. Now it’s not like that. Everything is done through money, and it’s much easier to control people through the reward and incentive of money. How much you make depends on how many pieces you make.”

Related Metrograph at Home Adds Major Films to Streaming in November

If you aren’t in New York, the great independent theater will bring the latest critical darlings to you through their streaming service.

Youth (Spring) is the most decentralized. Bing, of course, doesn’t provide narration, interviews, dramatizations, or any of the typical tools of documentaries. Youth (Hard Times) is a bit more focused, with a central story about a group of workers whose manager runs out on them, leaving them unpaid. Flanking that story are many other snapshots of working life. Finally, Youth (Homecoming) narrows the scope even more, focusing on some workers as they leave Zhili and return home, wherever that may be for them. By that time (about seven or eight hours in), we’re attached to the people and experience a kind of cathartic, overwhelming emotion with the shift from the gray, dank sadness of Zhili to the wide open landscapes and possibilities outside it.

A Groundbreaking Achievement in Time & Proximity

Time is a powerful tool in filmmaking. Rather than the quick edits of modern blockbusters, the brilliance of slow cinema is that it can lend itself to a kind of mesmerism. But it requires the right audience, and unfortunately, most people have been hardwired to rapid impatience. Frankly, Youth is going to bore most people within five minutes. You have to fight that urge and struggle with your own restlessness before you can fully travel into the richly human world of Zhili.

Related 25 Best Documentary Movies of 2022, Ranked

2022 was filled with amazing movies, and documentaries have been no exception. These are the 25 best documentary films of last year.

Eventually, over the course of hour after hour, as you hear the incessant buzz of the sewing machines, you become a part of it. You begin to empathize with the workers and understand the rhythm of their lives. You feel hopeless with the hopeless, and you latch onto certain people and root for them. You even get bored with them, watching them apathetically stare at a cell phone and watch some cute animated video that has no visible effect on their demeanor. Bing’s camera gets intimately (even intrusively) close to all these people, regardless of the tight spaces of their shared bedrooms and work spaces. Like the deep runtime, the deep proximity helps with the immersion and ultimate empathy. Bing told Film Comment:

“With this trilogy, I wanted to go back to the original purpose of cameras: as a concept to record, to chronicle, to document something. And that’s why I was vehement about this idea of being very close to my subject. This closeness is not only about physical closeness, but [emotional] connection, too, and how we connect on a human level. I wanted to capture everything, including the mundane and day-to-day moments. The only way I can do that is by following them for long periods of time. That way, I can really observe, document, record, and chronicle what they’re going through.”

Related 32 Best Documentaries on Netflix Right Now

Netflix has a plethora of hard-hitting and thought-provoking documentaries available for steaming this instant.

What an amazing thing, to sit in a theater and connect on an actual material level with people halfway across the world. Youth facilitates empathy with the workers of the world, and an actual understanding of what their lives are like. We bond in our subjugated status, in the indifferent repetition of our lives, in the hopes and dreams we likely won’t achieve, in the small victories and little loves we find. That’s the brilliance of a monumental epic like Youth, each film of which can be appreciated individually, but it’s the trilogy that transports us.

Beginning Friday, November 1, Youth (Hard Times), Wang Bing’s transporting and critically acclaimed return to the monumental Youth Trilogy, opens for an exclusive one-week NY theatrical run at Metrograph In Theater . Beginning Friday, November 8, Youth (Homecoming), Wang Bing’s final cinematic portrait of the lives of young textile workers in China, opens for an exclusive one-week NY theatrical run at Metrograph In Theater. Stream Youth (Spring) on Metrograph at Home. Check out the trailer for Youth (Homecoming) below:

You can view the original article HERE.