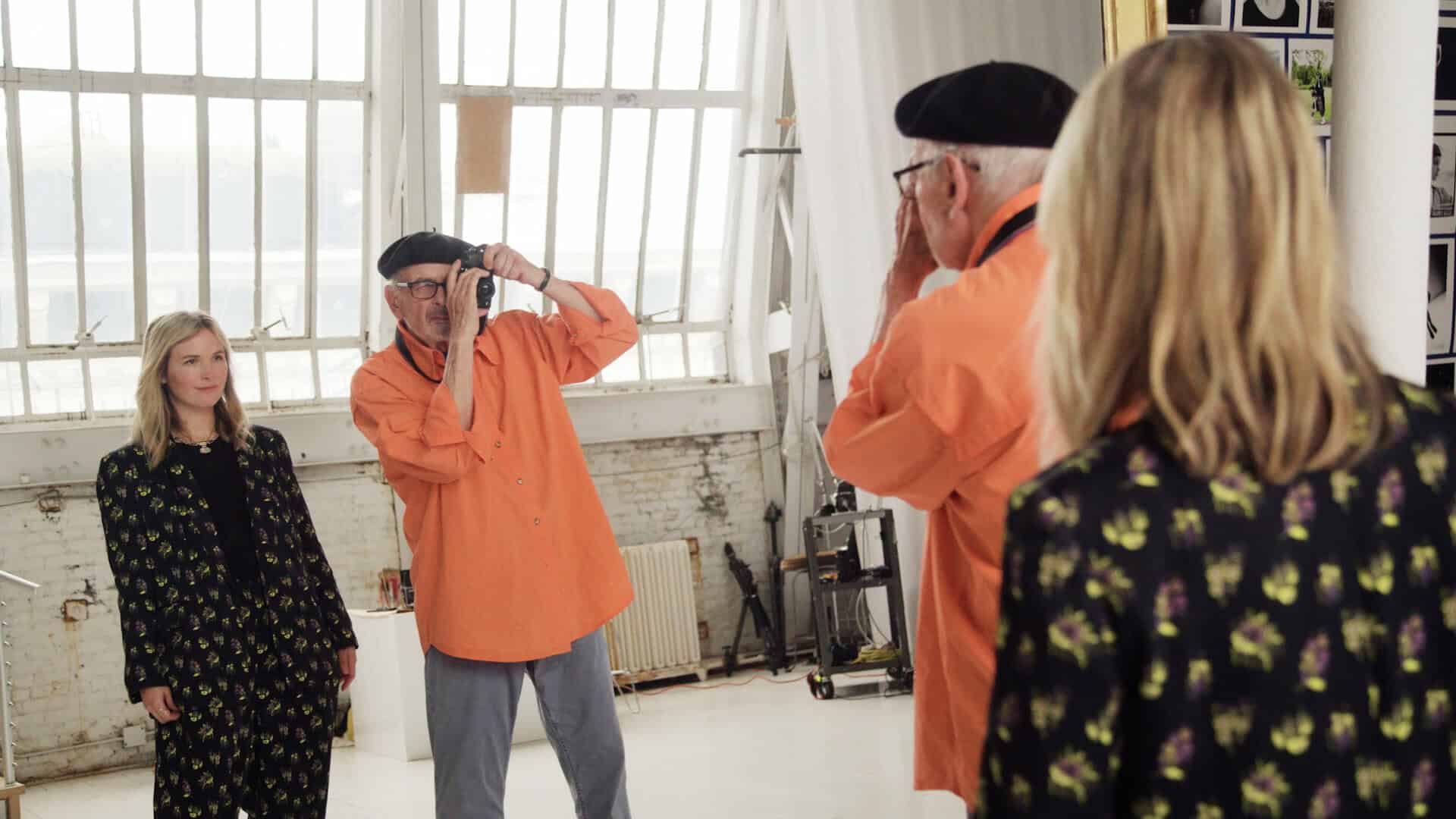

The great achievement of John Maggio’s latest HBO documentary, “A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks,” is the depth with which it delves into the nuance of indelible images such as these, which served as both vividly realized slices of life and artfully profound meditations on race. Maggio doesn’t simply gather a line-up of distinguished talking heads to inform us that Parks was important—he shows us why. We learn, for example, that Joanne’s niece had paused by the movie theater because she caught the aroma of the venue’s popcorn, which caused her aunt to become conflicted. As Ava DuVernay points out, Joanne resembles a radiant queen who is panicked by the notion of having to enter through a demeaning doorway. Though Joanne was unhappy with the fact that her shoulder strap had slid down her arm in Parks’ photograph, it’s a detail that magnifies how distracted and unguarded she is in this moment. It’s the vulnerability and humanity that Parks was able to illuminate in his subjects that makes his work as spellbinding today as it was when it was originally lensed.

“A Choice of Weapons” is named after Parks’ own autobiography, in which he detailed his upbringing in Kansas, where he found himself having to be a different person when in the presence of whites, a predicament he captured in his groundbreaking 1969 directorial feature debut, “The Learning Tree.” Encouraged by his mother to find a safer place to live, he toured the country while working as a waiter in the dining car of the Northern Pacific. His piercing and compassionate gaze never failed to find value in the lives of ordinary people, which stripped his subjects of labels such as “criminal,” as noted by DuVernay, who memorably filled the screen with that dehumanizing word in her own essential documentary, “13th.” While under the mentorship of Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration, Parks began documenting the life of Ella Watson, the Black cleaning lady at the agency’s offices. His photograph of her standing in front of an American flag as she holds a broom a la Grant Wood’s American Gothic speaks volumes about the mistreatment Watson endures from the country she loves. In another masterfully composed shot, Parks managed to capture four generations of her family in a single image by making exquisite use of framed pictures and mirrors.

Parks displayed enormous versatility during his immortal tenure as “the only Negro cameraman” on the Life Magazine staff. Though the Honorable Elijah Muhammad questioned why Parks would work for the “white devil,” he still allowed him to gain unprecedented access to the Nation of Islam in 1963, resulting in the photographer developing a brotherly connection with another towering icon, Malcolm X. When the pictures he took during this period wound up accompanying fear-mongering text in the magazine, Parks penned his own rebuttal, emerging as an activist. Yet he also saw the art form of photography as a weapon for change, a truth beautifully articulated in Maggio’s film by Ford Foundation president Darren Walker, who believes that once Blacks saw themselves as worthy individuals through Parks’ images, they demanded justice. Likening Parks’ weapon to a “motherf—kin’ bazooka,” Spike Lee made memorable use of the photographer’s Malcolm X portraits at the end of his essential 1992 biopic. Parks also utilized his lens to expose the impact of poverty on an emaciated Brazilian boy, Flavio, whose life was ultimately saved by donations made by readers. Once Parks’ own fame made it difficult for him to acquire the anonymity that enabled him to take candid pictures, he switched his attention to filmmaking and triggered—along with Melvin Van Peebles—the Blaxploitation genre. Editor Richard Lowe includes a priceless bit of archival footage where we see Parks explaining to Isaac Hayes how he envisions the film’s classic opening theme, which ultimately earned Hayes an Oscar.

You can view the original article HERE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/02/11/668/n/1922564/83cbbcca67ab667ee17e65.38091698_.jpg)