Fremont is truly one of the most special movies to come out of Sundance Film Festival this year. Possibly one of the most timely, too, given its themes of healing and moving forward (on both an individual and collective level). Indeed, on varying levels, we are all processing different types of grief, heartache, and trauma every day. Fremont doesn’t necessarily offer reprieve from the hurt, but instead revels in the sometimes achingly slow and winding process of starting anew. It’s a gem of a film that lets us know we are not alone.

Directed by Babak Jalali, Fremont follows 20-something-year-old Donya (Anaita Wali Zada), an Afghan translator who has been living in the eponymous Fremont, California ever since her work with the American military came to an end. Now, living alone in a neighborhood with other Afghan immigrants and refugees, Donya has found a job at a fortune cookie manufacturing factory. It’s an easy, if monotonous, life for her, but she has trouble sleeping. Things begin to change when she starts seeing a therapist (Gregg Turkington) and, later, gets promoted to writing the cookies’ actual fortunes at work. Inspired by the conversations she has with her doctor, Donya decides to type out a personal message in one fortune cookie, sending it out into the world, not knowing who might answer, but feeling excited about it all the same.

MOVIEWEB VIDEO OF THE DAY

An Understated Performance from Anaita Wali Zada

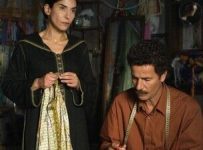

Butimar Productions / Extra A Productions

What’s most notable about Fremont is the sheer intention with which all involved approach to telling the story. Jalali and co-writer Carolina Cavalli’s decision to position the narrative from Donya’s perspective effectively rebukes the preconceived notion (often held by western viewers) that she, as an Afghan woman, is without choice. Far from it, in fact: Donya moves through Fremont, taking charge of an unclaimed doctor’s appointment, for example, or climbing the corporate ladder of the fortune cookie factory, in a way that is, perhaps for the first time in her life, very clearly driven by her own agency, needs, and desires. That Jalali cast Zada, who herself is an Afghan refugee with no previous acting experience, lends the film a poignant verisimilitude. Donya doesn’t say much, nor does she often outwardly react to what’s happening around her, but, at the same time, she’s never completely still. Zada’s performance is understated brilliance, everything bubbling just underneath the surface.

Related: Coming-of-Age Amidst the Epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Indeed, in any given scene, it’s Zada’s co-star who often drives the conversation. Turkington as Donya’s therapist and Hilda Schmelling as her exuberant co-worker Joanna are knockout scene partners, coloring Donya’s day-to-day. That said, Zada never feels lost in the mix. She’s ever-present, giving us access to Donya’s well of loneliness with a glance or the quirk of a lip, never letting us forget whose story this belongs to. Even when Jeremy Allen White stumbles into the third act of Fremont as Daniel, the sole mechanic at his shop, Zada holds her own. A far cry from The Bear’s Carmy, who is confident, serious, and isn’t afraid to charge forward, Daniel is awkward but charming. As the two characters circle each other, afraid to make the first move but desperate to do so as if their very existence depends on it, Zada and White are a joy to watch.

A Stunning Technical Achievement

Butimar Productions / Extra A Productions

On a superficial level, Fremont may feel like a simple film in premise and production, but it is deceptively a stunning technical achievement. Shot in black and white, cinematographer Laura Valladao’s lens is an invaluable tool to further understanding Donya’s interiority. She favors static shots and longer takes that often offer unobstructed, frontal views of the characters, which, backed by a contemplative score from composer Mahmood Schricker, allows for a meditative examination of guilt, anxiety, fear, and desire. Particularly when the camera faces Donya, it almost feels like looking into an emotional mirror: we may not look like her, but we also know what it’s like to be in her position.

In this way, Fremont becomes almost like the very fortune cookies Donya makes at work. The simple phrases scrawled across each slip of paper may not be exactly what you’re hoping for when you crack a cookie open — platitudinal at best, superficial poesy at worst — but you take whatever meaning from them that you can. Fremont ultimately asserts that life is messy, random, and bound to hurt, but it also reminds us that we gain nothing from standing by and letting it pass. It’s the notion of leaning in — leaning into the discomfort, into the people we meet along the way, into the silliness of a fortune cookie — that Fremont successfully channels, that we mustn’t forget. As Donya eventually learns, there really is beauty in the world around us.

Fremont just finished its run at Sundance. Prior to the festival, it was purchased by Memento International (via Variety), but a release date has yet to be confirmed at this time.

You can view the original article HERE.