James Mangold is no stranger to locking in on the finer rhythms of some of American music’s most indelible figures: His 2005 Johnny Cash biopic, “Walk the Line,” was a soup-to-nuts recounting of the Man in Black’s life in music, and in the same breath offering up a snapshot of the state of the American folk and country scenes in the 20th century.

Since then, he’s taken a nice long stretch in the blockbuster firmament, offering both well-hewn spins on classic dad-movie genres like the Western (“3:10 to Yuma”) and the racing film (“Ford v. Ferrari“), as well as taking high-profile turns in popular franchises with “Logan” and “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.” It’s the kind of flexibility A-list directors don’t often get to demonstrate, and a challenge that Mangold takes with remarkable elan.

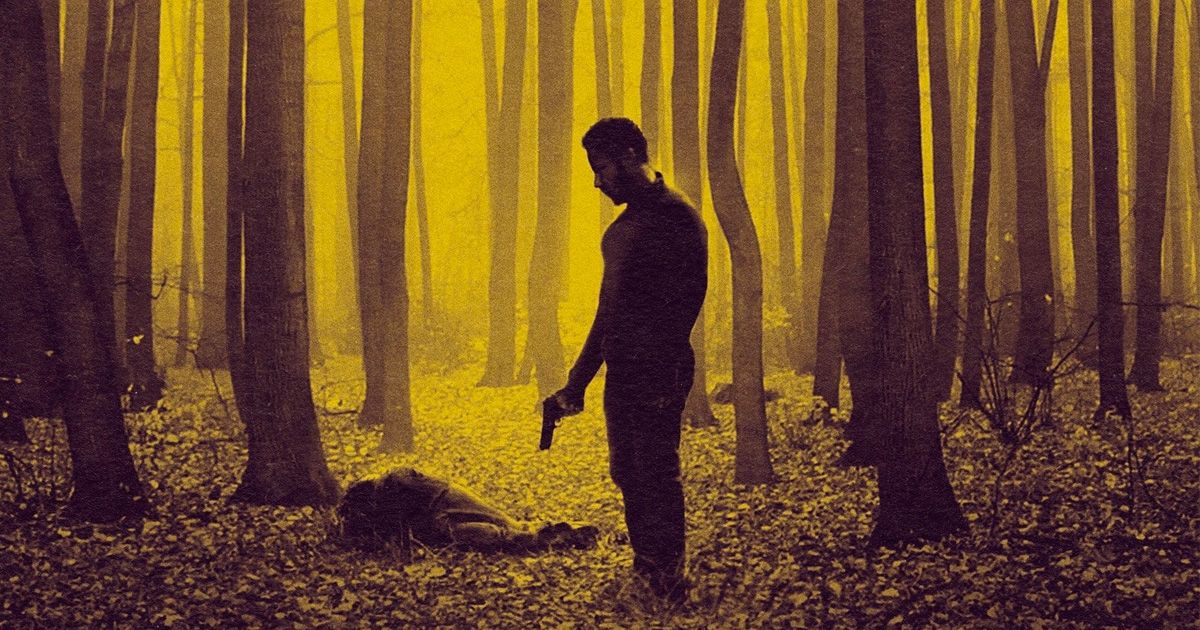

But with his latest, “A Complete Unknown,” Mangold shines a light on one of Cash’s most famous contemporaries, Bob Dylan, but takes a distinctly different tack to understanding the man. Rather than making him think about his whole life before he plays, Mangold hones in on a six-year period in Dylan’s early career—from the moment he rides into New York City with nothing to his name, hoping to impress a dying Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), through his ascendancy to folk superstar, to the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where he shocked his contemporaries and audiences by going electric and radically changing his image forever.

As with “Walk the Line,” “A Complete Unknown” feels like a singular collaboration between director and star—this time, Timothée Chalamet as a young Dylan, all shrugged shoulders and unassuming cool. Shuffling through the early ’60s on a wave of unexpected fame, Chalamet’s Dylan bristles against all the new attention he receives, both from throngs of screaming fans and the folk elder statemen (including Edward Norton‘s gentle, paternalistic Pete Seeger) who see him both as savior and threat to the sanctity of folk. And throughout, Mangold captures Dylan’s performing, both on massive stages and in intimate moments, with assured sequences that demonstrate Chalamet’s impressive evocation of Dylan’s inimitable voice, both spoken and sung.

Mangold spoke to RogerEbert.com about the long, winding road back to the form of the music biopic, wrestling with both Dylan and Chalamet’s rising stardom, and whether he thinks “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story” killed the music biopic.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This is you returning to the realm of music biopics for the first time in about twenty years—since then, you’ve made the rounds in a wide range of blockbuster filmmaking modes and genres. What brought you back to the music biopic, and Dylan in particular?

JAMES MANGOLD: Throughout my career, I’ve had this oscillating pattern of doing bigger and smaller movies with bigger and smaller budgets. I mean, even the first two movies I made—one was a slice of life rural picture called “Heavy” about an overweight chef and his blossoming. And the next year, I made “Cop Land,” which was more packed with stars and action, a kind of cop film meets Western with a cast like Sylvester Stallone, Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, Ray Liotta, etc. So it was a pattern of changing things up that came about naturally.

I kinda feel like it’s never stopped, in the sense that the only thing that stays the same is I write on all the movies and I direct them, and I bring whatever sensibility I bring. I don’t really shoot the big or the small any different, from my own point of view. It’s still moving actors around in a space and trying to make moments happen truthfully.

Beyond all that, the freedom I’ve had to make all these kinds of movies is such a joy, and another way that Bob Dylan inspired me. He’s never allowed there to be a box he won’t escape from. Whether it’s making folk music and then going electric, or whether it’s reversing direction and going back to a folk album, or releasing Christmas albums or touring. Even the great records he’s made in the last ten years, he keeps redefining himself. As he himself said on his last record, “I contain multitudes.” In my own modest way, I feel exactly the same.

That’s a central conflict with “A Complete Unknown,” too, Bob’s desire to reinvent himself, to evolve his sound, and the conflicts that come into play among his personal and professional lives. As you said, he’s had many eras; what made you want to hone in on this specific era of reinvention?

I thought it was a period of time in which a lot of it went unexplored. Once you hit 1965, that’s when the Pennebaker documentaries, the Maysles, and all that started to come in. But prior to that, he obviously wasn’t much of a star yet, and there wasn’t that kind of focus on him. There weren’t many interviews with him. That’s one of the openings I felt the movie offered us, a chance to depict and enrich the picture of a young artist at this formative, almost fairytale moment of arriving in New York with a guitar case and a Moleskine notebook filled with lyrics and notes and twenty bucks.

He’s very much a blank slate when we first see him—well, not quite, but he comes in not quite fully formed.

Well, he certainly is to the world of New York. He’s a complete mystery, but he invents a name and starts singing songs. When I first met with Bob Dylan, he asked me, “What is your movie about,” I said to him, in my mind, it’s about a young man suffocating in his hometown in Minnesota, leaving behind his family and friends and ventures 2,000 miles away to the biggest city in the country, penniless, with a guitar. Before long, he’s blossomed, invents a new identity for himself, a new name, makes new friends, finds a new family, and meets with tremendous success. Then he starts to suffocate again, and moves on.

In a sense, the movie, almost like a ballad, has a repeated refrain. It’s no coincidence that the film opens on Bob riding into down in the back of a car and ends on him riding [into] town on a motorcycle.

Searchlight Pictures

Speaking of the Pennebaker documentaries, I have to imagine a consideration was made between you and Timothée about the fact that we’ve seen so much of Dylan on screen already. Whether it’s himself or other people playing him. Was that anywhere in the static of what the two of you were doing?

The way you deal with that stuff is just moving through it. Sometimes, being a sports fan helps you make movies. Because in the end, you just have to get the ball down the field or put the bat on the ball. And if you think too much about what someone else did or is doing, you’re never going to meet the ball with the bat, because your mind isn’t on your task. You have to have faith that what you’re going to do will naturally be different because you’re doing it, whether it’s Timmy or myself or us in partnership, we’re doing something different you haven’t seen before.

In a way, when people see the movie, it’s not quite what they expect in the sense that it’s not this kind of impenetrably cool movie about an enigmatic, hard-to-know guy. There’s aspects of that, but I also feel like there’s a lot of commonality and approachability. You do actually understand more about him and his challenges in some ways. How hard it is when you’re blessed with a kind of volcanic talent that has you writing ten, fifteen of the most important songs of the 20th century between the ages of 19 and 23. That’s pretty incredible, and can also make you feel a little alone and under siege, with the celebrity and the kind of power that it creates around you. And how quickly many relationships become more transactional than pure.

Which I’m sure played in during production too. Much like Dylan at this point in his career, Timothée’s star is rising in a very meteoric sense, which might invite some parallels. What were your observations of that and how he’s handling it? Was that a consideration while you were filming?

The funny thing is, as a director and Timmy’s friend, there’s things you know about him pretty well. All the things you’re saying are true, but I didn’t discuss it much. It’s so obvious, you’re absolutely right, but the fact is that sometimes, those things are better left not being labeled. Clearly he understands what it’s like to be mobbed and have people feeling intense emotion about you and for you when you don’t even know them. Everyone who makes movies has this unique perspective, though obviously not on the scale of Dylan. We make these movies, we love what we do, and we present them to audiences. Very often, the reaction is adoring, and you don’t actually know what to do with it. Same is true when the reaction isn’t adoring.

It’s very challenging—not like a pain, but it takes adjustment, because it’s so asymmetrical. You have one side that has absorbed everything about your film or your performance, and they have so much feeling. But you don’t know anything about the person on the other side. It’s alien to normal human existence, of course. I’m sure the other actors in the film—Monica [Barbaro] playing Joan and Edward [Norton] playing Pete, all drew from their own trajectories and experiences as well.

Searchlight Pictures

Speaking of the supporting cast, I did want to talk about Norton as Seeger, because it’s such an interesting performance. Obviously, you have to affect a kind of mannerism and capture Seeger’s voice, but he also plays such a fascinating role as both mentor and nemesis to Dylan. Given how gregarious and gentle Seeger is, I’m curious how you and Edward worked together to find those moments where kindness and generosity bumped into the natural conflicts that happen between these two professionals.

The real story took care of that, you know? It’s such a kind of Shakespearean tale in a sense; you have this ailing folk hero in Woody Guthrie, this first lieutenant who’s shepherded the folk movement into a point of total ascendancy [in Seeger], but he’s missing the star that could put them over the top. Then out of the mist comes this young man with a name you’ve never heard and a little songbook. There’s so much talent in him, and Pete reaches for him and supports him and pushes him to the stage, where he takes off like fire.

But of course, that’s only the beginning. Because what happens to this young man after so much power and spotlight is shifted so singularly upon him, is that his dedication to folk music wasn’t ever as dogmatic and polarizing as Pete’s religious devotion to the concept of folk music. Bob would readily admit that he didn’t. He loves all kinds of music, and never had that kind of partitioned point of view that Pete’s had in so many ways. In the first ten minutes of the movie, you have the first major scene between Pete and Bob just talking about music; already, you can see the dividing lines of their philosophies, albeit in the friendliest, most innocuous way. You understand there that they don’t see things exactly the same way.

Then there’s Boyd Holbrook’s Johnny Cash as the devil on the shoulder, giving Dylan this permission structure to shake things up. What was it like revisiting that character for the first time since “Walk the Line”?

I love the idea of Johnny Cash [in the film], and it came about because he was pivotal. He carried on this long letter-writing relationship with Bob for years. In previous drafts of the script, Johnny just kind of cameoed at Newport but didn’t play much of a role. It made sense why Jay [Cocks, co-screenwriter] handled it that way, because they weren’t in the same space very often. But I was aware, partly from my research making “Walk the Line,” that they had this correspondence. So one day, while I was writing, I called up Jeff Rosen, Bob’s manager, and said, “Bob wouldn’t have those letters from Johnny, would he?” and he was like, “We absolutely do have them.” He sent them over to me. So the words that Boyd speaks as Johnny Cash in the movie are Cash’s words. They’re the literal letters that Johnny Cash wrote to Bob at those pivotal moments in his life.

What was it like revisiting the character? Freeing and also really gratifying because I really love Boyd. He’s a fearless actor. We never once discussed that I had made a Johnny Cash movie before. And he just dove in and became him.

While we’re on Cash, I’m curious about your thoughts about “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story,” which kind of poked and prodded at the typical rhythms of the music biopic largely through your prior film. How did you receive that film? How much have you thought about it? And did you think about any genre traps you wanted to avoid falling into with “A Complete Unknown”?

I have two thoughts about it. One is that I enjoyed the movie, and was flattered that someone would make the Mad Magazine version of our film, and I found it hilarious. But it also strikes me as particularly modern Internet thinking that, because someone satirizes a movie form, it goes extinct. That would mean that “Blazing Saddles” makes it impossible to make a Western, or that Guillermo should not make a Frankenstein because “Young Frankenstein” exists. There are hundreds of satirical films made about the slightly shopworn turns of plot in different genres. But that doesn’t mean the genre is dead; it just means you should try to reinvigorate the form.

One of the ways we did that with this movie was by not trying to be too much about dispensing information, not that I feel we overdid that with “Walk the Line.” No cameo roles of stars coming in and out. Making it a character piece, as if it was just a fiction film, in the sense you’re following a character through a few years of his life and a series of momentous events. There aren’t a lot of dates and places and times on the screen. There aren’t a lot of scenes where people say, “Music will never be the same,” or whatever the cliches would be.

But at the same time, I don’t think that making a humorous observation about things makes the original form extinct. Otherwise, about nine or ten genres would be completely dead by now.

“A Complete Unknown” enters wide release on Christmas Day, courtesy of Searchlight Pictures.

You can view the original article HERE.